in the housing market

Download this article as PDF here.

Longstanding structural racism embedded in housing markets has segregated housing,

leading to disinvestment and the devaluation of Black-majority neighborhoods. But that’s only half the story.

Structural racism in the housing market also harms Black residents when the long cycles of disinvestment finally end, and those neighborhoods ultimately attract investment, as is happening now in cities across the US.

As investment dollars find their way in, historically Black and mixed neighborhoods are rapidly becoming gentrified, and Black residents are increasingly getting priced out. Just when neighborhood development, appreciation, amenities, and services that they have been denied for decades finally kick in, they are excluded from the benefits.

For example, Black-majority Baltimore is one of the five fastest-gentrifying cities in the U.S., yet it also has historically Black neighborhoods so deeply and chronically devalued and disinvested, that despite explosive development in other parts of the city, they remain full of vacant and dilapidated housing, and get none of the benefits of the investment pouring into other neighborhoods. In many other cities, gentrification is driving up housing prices so rapidly (in Tulsa, Oklahoma, prices rose 34% in 2021 [i], notwithstanding the pandemic) that it’s displacing Black residents at alarming rates.

In an attempt to fight displacement and create more housing density and equity, some cities (Seattle, Portland, and others) are “upzoning” — rezoning neighborhoods with predominantly single-family housing for multi-family housing. But that raises existing property values and property taxes, which drives up existing homeowners’ costs and tends to force more Black owners in these neighborhoods to sell.

It’s an ironic double bind: either chronic disinvestment continues to hollow out Black communities from the inside, or else new investment raises housing costs and displaces them. In both cases, Black residents stand to lose not only their homes, but the coherence and social capital of the neighborhoods they call home.

By itself, separated from the long history of housing discrimination, devaluation, and dispossession Black people have experienced, neighborhood development is good, necessary thing. Why can’t we create development that benefits Black residents instead of displacing them? What would it take to achieve what one community development organization calls “gentrification with justice?” How would the housing market have to be restructured in order for more Black residents to become full stakeholders in the successful development of the communities where they live, and share in the benefits as neighborhoods become more attractive and prices rise?

Community land trusts (CLTs) are described in another paper in this series, “Evolution in Community Land Trusts.” They are designed to resist gentrification, preserve affordable, secure housing and fight displacement by separating ownership of a home from the ownership of the land it sits on. That’s one way to enable development without displacement in neighborhoods under pressure. But it’s not the only way.

New models are emerging that bear comparison with CLTs, but have features and solve problems that CLTs don’t. Like CLTs, they enable community-led development, create affordable housing, fight displacement, and help preserve the character and coherence of Black-majority neighborhoods. But they leverage the structure of homeownership in different ways than CLTs do.

This paper describes three such models. One renovates and sells whole blocks of housing to groups of homeowners instead of selling single-family housing to individual buyers. Another helps single-family owners develop multi-family housing on their properties. Another makes renters co-owners of a trust that keeps their rents low, but still enables them to benefit as the neighborhood develops and appreciates, just as homeowners do.

These experiments are small in scale and still in the proof-of-concept stage. They are potentially scalable, but their impact is less about reaching scale themselves than about the pathways they model for redesigning market structures to enable development without displacement, preserve and enhance Black communities, and give more Black residents an economic stake in their success.

Baltimore’s Gentrification Dilemma

Baltimore is a Black majority (63%) city with a history of restrictive covenants, redlining, disinvestment, and other forms of exclusion which led to segregation and devaluation of Black neighborhoods. Its poverty rate (23.1%) is almost twice the national average, with far higher rates in Black-majority neighborhoods and far lower rates in white-majority neighborhoods.

Yet with its historic waterfront and proximity to the Capitol area, Baltimore is now one of the five fastest-gentrifying cities in the U.S., along with New York, Los Angeles, Washington, DC, and Philadelphia. Not surprisingly, an Urban Institute study found that private investment concentrates in Baltimore’s whiter, wealthier neighborhoods, which attract most of the building permits, rehabbing, and financing for residential and commercial development.

Significant public and mission-driven investment has been focused on Black-majority neighborhoods, but it’s small amount of money compared to the private capital driving the city’s overall development. As a result, despite intense gentrification in some parts of Baltimore, development has bypassed other Black-majority neighborhoods.

West Baltimore is a case in point. It is a historically important Black neighborhood, located under an hour from Washington, DC. For many decades it was a prosperous, economically diverse community. But like many other Black communities nationwide, starting in the early 1940s, a combination of redlining, housing segregation, urban “renewal,” job discrimination, loss of blue-collar jobs, and successive drug epidemics forced it into decline.

Today West Baltimore has a reputation for dilapidated housing, crime, and as the scene of the 2015 death of Freddie Gray in police custody and the uprising that followed it. Six officers were indicted on charges including second-degree murder and manslaughter, but none was convicted. Largely peaceful demonstrations boiled over; buildings and cars were burned. Protestors expressed their outrage at longstanding, systemic injustices from police brutality to economic disparity. Median income in Gray’s West Baltimore neighborhood of Sandtown-Winchester/Harlem Park neighborhood is just $24,000, more than half of residents don’t have jobs, and a third of the housing is vacant or abandoned [ii].

While that’s many people’s image of West Baltimore, it’s inaccurate. Its neighborhoods are rich in history, culture, social fabric, and housing stock with beautiful architectural details, plus it has the most generous greenspace of any neighborhood in Baltimore. All things being equal, these valuable assets should make West Baltimore an attractive place to live, including for Black residents displaced from other parts of the city by gentrification, and a good candidate for development.

Yet developers have mostly passed it by, partly because it has large areas of unmaintained and/or vacant, unlivable housing. That raises risks and costs for developers and homeowners, and depresses property values and housing demand. And as long as developers stay away, disinvestment, devaluation, and associated social problems persist in a vicious cycle.

But even if developers did decide to invest in West Baltimore, what’s to prevent them from buying up large swaths of devalued property, gentrifying them, and forcing Black residents out, as was done in other parts of the city? How can neighborhoods like West Baltimore attract needed development without stoking displacement?

Rebuilding a Distressed Community Block by Block

Bree Jones is pioneering a way to bring development without displacement to West Baltimore.

She’s the CEO of Parity, an equitable development company proudly headquartered there, and embedded in the community.

Parity’s tagline is, “Where some see ruin, we see beauty.” Beyond West Baltimore’s seemingly intractable problems – disinvestment, devaluation, abandoned and deteriorating buildings, crime, fraying social fabric, a stymied housing market few would buy into — Jones recognizes the underlying value of the neighborhood, and works to demonstrate its potential as a viable market and an attractive, connected community.

“I’m working in one of the most distressed neighborhoods in the whole city,” Jones says. “When you view it through a historical lens, and you really understand the impact of redlining, racial segregation, blockbusting, white flight, predatory lending, eminent domain, urban renewal and so forth, you realize it all creates an economic handicap in historically Black neighborhoods that make development next to impossible.”

“The housing market here is gridlocked because there is a glut of housing stock and supply that’s unlivable, which further fuels vacancy. So my model is to unlock those gridlocked housing markets by leveraging social capital.”

– Bree Jones, CEO, Parity

Parity creates affordable homeownership of newly renovated properties in West Baltimore, taking what Jones calls a “collective economics” approach. The term means leveraging the mutual goals or preferences of a group to secure economic gains for the whole group [iii]. That can change the economics of a market and can lead to structural innovations that go beyond finding greater efficiencies or economies of scale.

Instead of rehabbing one house at a time, Parity’s innovation is to buy and flip whole blocks in distressed areas, and recruit groups of new owners who are already socially connected and willing to buy in as a collective, and to move in at more or less at the same time. They bring their own social capital with them, creating not just blocks of affordable housing, but blocks of connected communities.

Neighborhoods with many vacant or run-down buildings impose heightened risks and costs on nearby homeowners — anything from driving down their property values to spreading pest infestations to them. But by moving into a block as part of a group, each Parity homeowner reduces those risks and costs for the others.

At the same time, by moving in as a group, they kick-start the re-weaving of neighborhood coherence and connectedness which might otherwise take many years to accomplish. Buyers get the full advantages of fee-simple ownership of their individual properties, including stability, equity, and wealth building. But they also get the collective value of neighbors, greenspaces, and a network of community connections in a place they can call home.

“These social groups are friends, families, church congregations, teachers, PTA groups, firefighters from the neighborhood, from the city, and from other areas where displacement has pushed people out” says Jones. “We’re basically utilizing existing social networks and social fabrics. We’re saying to them, hey, let’s all build up this neighborhood together. Then you’ll know your neighbor, you can go next door, knock on the door for a cup of sugar.”

All prospective buyers must undergo a six-month training which Jones designed, to make sure they understand and align with the goals of the program. “We talk a lot about our principles of anti-displacement, intersectionality, and being mindful of people’s different lived experiences, because this program is not just for college-educated folks,” Jones says. “We also talk about what it means to be civically engaged, and how to advocate for yourself and your community, and what to be aware of as a homeowner – even little things like clearing the lint out of your dryer. If you’ve never owned a home before, it can be life changing. So after those six months, our folks come out of the process rooted in equitable community work, plus they get financially and mentally prepared for homeownership.”

A partnership with Neighborhood Housing Services provides homeownership counseling and financial literacy help for prospective buyers. Parity has also built relationships with Bank of America, PNC Bank and other local banks in the neighborhood, so they work with homebuyers to help them qualify for a mortgage and get them preapproved. Once preapproval is given, the buyer puts down $5000 plus escrow, and the renovation begins. Six months later, the mortgage is issued and the new owner moves in, becoming part of a community with the other homeowners in their group.

Parity rehabbed its first block of housing with 25 prospective homebuyers from mostly low- and moderate-income backgrounds between the ages of 25 and 65. It owns nine properties, with another 15 in the pipeline. As developers go, that’s small-scale. But there’s pent-up demand for Parity’s approach. Even with little marketing so far, it already has a long waiting list of people interested in buying and moving to homes in West Baltimore in groups.

“It’s been entirely organic,” says Jones. “It started with me going to neighborhood meetings and speaking at panels, then someone comes up to me afterwards and says, this is awesome, I want to join the movement.

In just 12 or 18 months, we’ve flipped the real estate situation in the neighborhood on its head. Whereas before there was more housing supply than demand, we actually now have more demand for our housing than supply.”

Parity is now very intentional about outreach and sees what Jones calls “storytelling” as essential to the success of the model. “Communities like ours really need a story or the brand that communicates the vision of what they can be, why people would want to live in them,” she says. “People move to hipster neighborhoods for the coffee bars and yoga studios; it’s part of the brand. For our communities, you have to tell the story that makes people want to come and invest. We’re working to do that in an authentic way. We’re doing a ton of content creation, videos, social media.” Parity is hiring a head of storytelling to formally oversee the process.

Jones anticipates that a surge in demand will result. Meeting it will require more capitalization so Parity can acquire and rehab more properties. Its current finances are split between equity, debt, and subsidy, including a $1.5 million term sheet with Prudential Impact Investment, which partnered with the Kresge and Annie E. Casey Foundations to provide loan loss reserves. Parity has another $400,000 line of credit with the corporate social investment organization Reinvestment Fund. Both credit sources are revolving; they get replenished whenever Parity sells a home, and redeployed for the next project. By revolving the lines of credit six or eight times, Parity has enough financing to buy and flip 10 city blocks containing 96 homes.

But keeping them affordable for homeowners depends on subsidies. “That’s the last segment of the financing, and it’s really critical,” says Jones. “There are no federal low-income housing tax credits for homeownership. So subsidies have to come from city and state sources, foundations, or charitable givers.” So far, Parity has received $200,000 from the State of Maryland, several hundred thousand in grants from foundations, and $150,000 from private donors. Those funds subsidize the home prices, enabling Parity to offer newly renovated housing in historic buildings for $5000 down and monthly payments as low as $921.

“But it’s not enough to just create new homeownership and new wealth,” Jones says. “We really need to retain and protect legacy wealth, too. We do community organizing to build bridges between legacy residents and new residents, so that new residents don’t push people out, or assume that their wants take priority over people who have lived there for many years. And we connect legacy residents with displacement prevention services like pro bono legal assistance, life estate plans, family mediation, and homeowners tax credit applications. Last year we raised $85,000 in a mutual aid effort to bail out 56 low-income, disabled, or elderly homeowners from a tax sale, where they ran the risk of losing their homes for unpaid property tax debts as low as $750.”

Scaling up the Parity model will require raising more money for both capital expenditures and operations. Jones hasn’t been able to pay herself a salary yet, though she was selected as an Open Society Institute Fellow and received the Johns Hopkins University Social Innovation Lab Prize funded by Abell Foundation. And she has also been approached by other developers who want to understand and replicate Parity’s success in generating robust demand for West Baltimore housing, which could be a fee-for-service opportunity. Community development organizations are interested in applying Parity’s approach to leveraging the assets of other communities suffering from a lack of investment and development . That could be another non-capital-intensive way for Parity to extend the reach of its model.

But as the approach catches on and housing demand rises in distressed communities like West Baltimore, it could also attract the attention of speculators and raise the danger of gentrification. Jones has witnessed this phenomenon herself, having grown up in the Bronx, a distressed community now getting gentrified. Her goal is to preempt gentrification, and harness development pressures to serve Black residents instead of forcing them out.

“A lot of historically Black communities will stay dormant for 20, 30, 40 years,” she says. “There’s no activity happening, and then suddenly, boom, gentrification. And then it’s too late, and people get displaced. So we work in historically Black neighborhoods that still have zero housing development and develop them preemptively in a way that’s community-led and creates ownership of the process, so we’re actually strengthening the neighborhood against gentrification.”

“Preemptive development” is a smart tactic for heading off gentrification, but it’s also much more than that. It’s a structural innovation, a way of redesigning market structures that have kept Black communities disinvested, devalued, and walled off from development, then eventually opened them up to speculation, gentrification, and displacement. Parity found a hack for these market failures by invoking the power of collective economics, rehabbing whole blocks instead of individual properties, and attracting whole communities of buyers instead of individual owners.

That idea has potential to change housing markets in West Baltimore and elsewhere in far-reaching ways, because it represents a fundamental shift in who buys in (collectives as opposed to atomized individuals) and what they buy (connected neighborhoods as opposed to individual homes).

But it still doesn’t eliminate perverse incentives for speculators to come in and drive prices up once people start moving in. Changing those incentives would require more structural innovations. “Our sweet spot is acquiring land and properties where we’re not going to get into bidding wars with speculative investors,” Jones says. “But ultimately, once we start market activity, I can’t stop them from coming in and trying to find properties and plugins. And so I think a lot about ways to mitigate that danger.”

Besides developing affordable housing block by block and helping existing residents stay in their homes, Parity also fights gentrification through policy advocacy. For example, Jones is working with the community to develop a master plan for development, which will be recognized and adopted by the City. Any large-scale development project in West Baltimore would have to conform to it, and the developer proposing it would have to be approved under the plan. She’s also advocating the abolition of real estate tech sales for owner-occupied housing, because they often take advantage of owners and accelerate transfer of their properties to speculators. And she is thinking about other mechanisms to protect communities against gentrification, like zoning overlay districts.

Jones believes creating new, widespread ownership opportunities while keeping existing owners in the neighborhood can strengthen communities sufficiently to fight off gentrification, enabling them to leverage the benefits of development for themselves.

“Where there’s lack of ownership and lack of housing stability among community members, it’s like soil without trees or grass or roots. It’s really easy for that soil to erode. But when you strengthen ownership and housing stability, residents can put down roots, and the community grows strong.”

– Bree Jones, CEO, Parity

For now, her work is in the proof-of-concept stage, with Parity renovating and selling just a few blocks so far. But small-scale implementation notwithstanding, the concept itself is a powerful lever for bringing community-led investment to vacant or distressed areas, nourishing a community’s roots, and preserving its social capital. It’s a model that could potentially be replicated in many devalued Black neighborhoods.

Upzoning and Displacement in Seattle

Seattle is a prosperous city with a robust job market. But it also has a long history of racial segregation and discrimination whose legacy still restricts Black residents from sharing fully in its opportunities.

Racist policies long excluded Black workers from good jobs in Seattle. For example, Boeing and the union that represented its workers long maintained white-only hiring policies, even when labor was in high demand, relaxing them only under intense pressure from the federal government during World War II.

Schools remained segregated through the civil rights era, prompting organized school boycotts in 1966. Restrictive covenants preventing prospective Black homeowners from buying homes in certain areas of Seattle were on the books until 1968. Starting with Seattle’s first zoning laws in 1923, zoning was designed to keep large areas of Seattle priced beyond the reach of Black homebuyers. A 1964 ballot measure would have outlawed racial discrimination in selling or renting housing, but it was rejected by voters.

These policies erected a formidable set of obstacles that prevented Seattle’s Black residents getting a quality education, earning a good living, or living where they chose. The effects continue to reverberate today. One of them is the continued overwhelming prevalence of detached single-family homes in Seattle, and a dearth of multi-family housing. Today, 75% of Seattle’s land is zoned for single-family homes, which comprise 81% of the city’s housing.

That makes Seattle inherently resistant to recent City policies designed to encourage more diverse neighborhoods. “Given its racist origins, [Seattle’s] single-family zoning makes it impossible to achieve equitable outcomes within a system specifically designed to exclude low-income people and people of color,” the research institute PolicyLink wrote.

On the other hand, phasing out single-family zoning in Seattle is a politically fraught proposition. One 2015 commission report that toyed with the idea was leaked to the press and caused a firestorm of opposition. But in 2019, in an attempt to mitigate the zoning problem, the City went ahead and upzoned certain single-family areas to multi-family.

This had unintended consequences, however. It made the rezoned land more valuable, which attracted more speculation, fueled gentrification, and raised property taxes. This happened despite the City imposing Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) requirements on upzoned areas. MHA mandates that new development must include affordable housing units or contribute to an affordable housing fund. But it doesn’t change the basic structural impetus upzoning gives to gentrification, or the negative side-effects of making land more valuable and taxes higher.

Since relatively few Black residents are in a position to benefit from higher land values by redeveloping their properties as multi-family residences, upzoning ironically threatens to force them out of the very areas where the City sought to redress discrimination. That’s why the Seattle Coalition for Affordability, Livability, and Equity (SCALE) is fighting it, despite upzoning’s good intentions. As SCALE’s Toby Thaler said, “If you goose gentrification, you’re not going to get homeownership for poor people in the city.”

Making Upzoning Work for Residents

In Seattle, a predominance of single-family housing combined with other discriminatory practices has long kept Black residents out of many neighborhoods.

To change that, the City took the necessary step of rezoning certain neighborhoods from single-family to multi-family. But “upzoning” as it’s called also increases the assessed value of properties, driving up property taxes, which tends to displace Black residents already living there.

It’s a widespread dilemma, and a growing one. Seattle, Portland, New York, and Los Angeles have a combined total of 1.7 million single-family homes. In fact, most urban housing in America consists of single-family homes. Many of them are owned by people with limited income who are vulnerable to being forced to sell as upzoning drives up their property values and taxes. Portland recently upzoned some of its single-family neighborhoods, and more cities are following suit to create more density as single-family homeowning Baby Boomers age and they or their families become more likely to sell.

But despite higher property values, selling is often not a good deal for these homeowners. They have built equity in their homes, often over many decades, but it’s a highly illiquid form of wealth. Sales forced by higher costs or the sudden need to cash out rarely bring sellers a price that reflects the home’s true value. That value isn’t only what the property is worth as a financial asset, it’s also the value of the home as a secure place to live, and the neighborhood with its community ties and social capital. In distressed sales, whether prompted by reaching retirement age or by upzoning, homeowners typically get back only part of the first form of value, and lose the other two, which are hard to replace.

In theory, upzoning should create more housing in cities and more opportunities for Black residents to live where they choose, including in neighborhoods where they have put down roots. But in practice, it can fuel gentrification and displacement, which often occur in neighborhoods where Black families have owned their homes for generations.

Parents or grandparents may have bought the home half a century ago, but when the neighborhood gets upzoned and families need to sell, developers may buy them out at a reduced price, convert the property to multi-family housing, and sell it for many times their purchase price. In that case, the former owners lose the value of the property’s appreciation to the developer, along with their home and their community.

The problem is getting worse as more Boomers reach retirement age. But a group of young innovators from MIT has designed a solution. Frolic is a small company that was born out of research done at MIT School of Architecture and Planning and the MIT Center for Real Estate. It works with upzoned property owners facing displacement to develop their formerly single-family lots into multi-family cooperatives. The owners get to stay on their land, but instead of just a single housing unit on the property, they develop multiple units, building a community where there was previously just a house.

The name “frolic” was borrowed from the Amish practice of barn-raising, where many families come together to build a large barn in just a week. The MIT Frolic model takes a similarly collective approach by helping a community take the assets it already has (land, capital, and interested homeowners) to build their future and plant roots in their neighborhood. Together, they build multi-family developments of six to ten households on formerly single-family lots.

Frolic works with owners to design and permit the multi-family project for much less upfront capital than would be required otherwise, creating affordable homes and higher density in a gentle, community-oriented way. The homes can be purchased with down payments of $5000 – $20,000 (average down payments on Seattle are about $100,000), and monthly payments are at or below market rent, enabling families who have been renting for generations (known as “generational renters”) to buy a home and build wealth.

The model was conceived by former MIT students Tamara Knox, now Frolic’s CEO, and Josh Morrison, now Frolic’s CCO (Chief Creative Officer), and designed with help from over 180 experts in housing, policy, and finance. “We both saw the challenge of how unjust change in cities can be, particularly as neighborhoods densify,” Morrison said. “A lot of our early thinking was about how to allow neighborhoods to change with grace and softness, driven by the people who live in that neighborhood experiencing the change. This required rethinking the development process from the ground up.”

At MIT, they spent two years studying various design, finance, and ownership models across the U.S., and then in Germany, Denmark, and Sweden, adapting elements of them into a model they launched in 2019. It’s currently being piloted in Seattle, focusing on the Central District, a historically redlined neighborhood where Black homeowners now face displacement due to upzoning.

“Many lots in the Central District now allow for greater density,” said Morrison. “That has driven up their land value and their property taxes. One of our homeowner’s monthly property tax assessments went from $350 to $620 since the rezone. But the price she could get if she sold has increased only modestly. Developers may build two or three luxury townhomes on those lots like hers that each sell for over $1 million dollars. Yet homeowners who sell to those developers can’t afford to buy another home in their neighborhood and are forced to move far outside of Seattle. This is tearing the Central District community apart.”

It’s therefore attractive for homeowners who want to stay in their neighborhoods to work with Frolic to build more density on their lots. Some owners they work with wanted to develop multi-family units on their upzoned property, but couldn’t figure out the financing or identify a developer to partner with until they found Frolic. Others were new to the idea, but embraced it as a way of helping their community and creating a rich living environment for themselves. “It’s like helping people dream about how they want to live,” says Knox. “They realize that their friends and their children can live in the units next to them, and that this is an opportunity to give homes to people in their neighborhood who are moments away from being displaced.”

“We are taking the new value generated by the rezone and putting it in the hands of the existing community,” says Morrison. “One of our homeowners – let’s call her Patricia — considered selling her home to a developer. This developer would have had to pay $750,000 for her property, and then invest another $300,000 to design, engineer, and permit a project on her land. All of this takes time, and developers need to compensate themselves for their risk with enough profit. So they build luxury homes that have high margins.”

“But with our model, Patricia can leverage the $450,000 in equity she has in her home to build a $3.7 million project with only $300,000 of extra capital, which we source from the local community. She stays in her home while we design and permit the project. She has a long list of people from her community who want to buy one of the seven homes being built on the property, which means that we as the developer don’t need to do guess-work. We can actually design the project to meet the price point and needs of the future residents, because we know who they are. All of this translates to a lower end-cost for our residents.”

In the Frolic model, small, thoughtful projects take shape on average-sized lots and affordable units sprout up around the neighborhood for just $300,000 – $400,000 of additional equity per project. Knox and Morrison believe that adding density without requiring large upfront capital or being reliant on subsidies or philanthropy is the key to making the model scalable.

They created a mechanism to collect the necessary capital from neighbors and community members, so that the financial upside of the investment stays within the local community. Community equity is supplemented as needed with capital Frolic is raising as part of a $10 million revolving fund.

Frolic projects are built and run on an “at-cost” basis, so there are no profit margins to raise development costs or ongoing monthly expenses for residents. Partnering with property owners eliminates the need to buy property and drives costs down further, cutting the amount of upfront capital, risk, and time required to build the project compared to conventional development.

To keep down payments low, Frolic uses a cooperative model, where the co-op owns the project as a whole, with one share for each unit. A resident buys their share, which gives them ownership of a specific unit within the project. “What’s unique about co-ops is that they allow for multiple layers of debt,” says Knox. “The co-op as a whole can take out a loan, called a blanket mortgage, and each resident can take out a smaller loan to purchase their share. Co-op shares in our projects cost between $100,000 and $400,000, and a resident can purchase them for 5% down — between $5000 and $20,000. Each month residents pay off their personal mortgage and a monthly co-op fee, similar to a homeowners association fee. The co-op fee pays off the blanket mortgage, utilities, and other shared expenses.”

“We are able to offer homeownership to families who have been renting for multiple generations,” says Morrison. “Their down payment is close to the typical upfront costs renters might have to pay. Their entire monthly housing expenses are the same as or less than what they were paying in rent. But unlike renting, they get to build personal equity and credit. They are creating a financial legacy for their children and accessing the economic safety net of homeownership that has historically been the backbone of the American middle-class.”

The multi-family properties feature shared spaces, including a common house with a communal kitchen and dining area, and a guest suite. By sharing these common areas, each resident gets the benefit of a larger home, but without the underutilized space and higher cost of a large single-family property.

Frolic’s team is dedicated to quality design, and making the experience of living in their projects a rich one for residents. “We design the projects to create moments of human interaction,” says Knox, “You have a fully private home which is your own. At the same time, you have all of these beautiful common spaces that allow neighbors to share moments of daily life. It creates the opportunity for spontaneous connections – the chance for an elderly couple to take care of their neighbor’s kid after school, or for young kids to have playmates that they can walk to without relying on their parents to drive them.”

Currently, with two pilot projects underway, Frolic has a development pipeline of 36 more projects in Seattle. These new projects represent over $15 million in homeowner equity and will enable 150 families to own a home in their neighborhood for the first time. And without any active marketing, there’s a rapidly growing waitlist. “Every day we’re getting people coming to us either wanting to develop their property or live in one of our projects,” says Knox. Frolic is building an ecosystem of lenders, developers, architects, residents, and property owners to help more people and organizations to streamline new projects. It’s working to license its legal and financing structure to other mission-aligned organizations across the country interested in replicating the model, including community land trusts.

For now, Frolic remains a start-up with just a handful of projects, but its biggest potential impact is not the scale the organization can reach on its own; it’s the power of its model.

Frolic represents a new approach to homeownership which counteracts the perverse effects of upzoning, creates secure, affordable housing and enabling residents to build wealth and community. Those are outcomes cities across the U.S. will increasingly need.

Since most of urban housing is single-family, and since upzoning will accelerate as Boomers age, Frolic’s model a potential market of millions of properties.

Displacement in Tulsa, from Race Massacre to Disinvestment and Gentrification

Displacement in Black majority neighborhoods often stem from deeply rooted, complex, historically layered problems that require deep, structural solutions. A dramatic example is Tulsa’s most famous Black neighborhood, Greenwood, once known as for its thriving businesses and prosperity.

Originally envisioned as a territory for relocated Blacks and indigenous people, Oklahoma became a state in 1907. After oil was discovered there, Tulsa had so many wealthy Black residents that Greenwood became known “Black Wall Street.” But May 31 to June 1, 1921, Greenwood was the scene of the Tulsa race massacre — the worst such incident in US history up to that time. Mobs of white Tulsa residents, some of whom were deputized and given weapons by police, attacked and looted Greenwood homes and businesses. Firebombs were dropped from airplanes. As many as 300 Black residents were killed, 700 wounded.

It’s remarkable how much of the massacre and its aftermath revolved around destroying and acquiring Black-owned assets and asserting control over where and how Black people lived. Most of the buildings in the neighborhood — 36 blocks — and over 1200 were homes destroyed. The property damage is estimated at well over $30 million (in 2020 dollars). More than 10,000 Black residents were left homeless. Those who didn’t leave the city were moved into Red Cross tents where they lived for over a year. Black people who lived and worked in white neighborhoods as domestics were also beaten and dragged to the tent camps. Once in the camps, they weren’t allowed to leave without the permission of white employers, and when they did leave, they were forced to wear green identification tags. Nearly 8 million of these tags were issued in the year following the massacre.

Greenwood’s Black survivors were determined to rebuild, but the City hastily rezoned the neighborhood and rewrote building codes to stop them, largely by making it prohibitively expensive. Then a Klan-led City commission unveiled a master plan for the Black neighborhood to be relocated further north, leaving Greenwood’s valuable land to be redeveloped by the City. Later, it came to light that white businessmen had unsuccessfully tried to buy parts of Greenwood in the years leading up to the massacre.

Many Black residents rebuilt their homes and businesses under cover of darkness, defying the new rules, and in the 1920s Greenwood bounced back. But beginning in the 1930s, redlining made it difficult for Black residents to own property there. A raft of discriminatory housing policies combined to devalue Greenwood real estate, making it a prime target of urban “renewal.” A tangle of major highways and a ring road were built during the late 1960s and completed in 1971, slicing up Greenwood and the adjacent neighborhood of Kendall Whittier. “What the city could not steal in 1921, it systematically paved over 50 years later,” wrote Smithsonian magazine on the centennial of the massacre.

The Kendall Whittier neighborhood adjacent to Greenwood was a busy shopping district from the late 1920s through the 1950s, until it was bisected by the same highway project that also decimated Greenwood. By the early 2000s, Kendall Whittier was known for vacant storefronts and adult-oriented businesses. By 2010, its occupancy rate had fallen to 35%.

But community development and business recruitment and retention efforts turned that around. Kendall Whittier Main Street attracted $158 million in private investment and opened 40 new businesses since 2013. The neighborhood now has galleries, breweries, restaurants, and boutiques. The occupancy rate has rebounded to 100%. But at the same time, rents are rising, affordable housing is scarce, and lower-income residents are getting priced out.

“The investments have come to fruition,” says David Kemper, CEO of the non-profit Trust Neighborhoods. “But one of the unintended consequences is they displace the very renters and residents they were trying to benefit in the first place.”

Giving Renters a Stake in Neighborhood Development

The turnaround of Tulsa’s Kendall Whittier neighborhood from vacant storefronts to a trendy destination with 100% occupancy is a success story.

In fact, in 2020 Kendall Whitier was one of three winners of the national Great American Main Street Award (GAMSA) for excellence in comprehensive preservation-based commercial district revitalization. “In just 10 years, Kendall Whittier Main Street has radically changed the perception of the neighborhood and become the center of community life for its residents,” said National Main Street Center President and CEO Patrice Frey.

So why can’t markets be designed in such a way that lower-income Black residents are able share in such success instead of being displaced by it? It’s a familiar dilemma for a disproportionate number of Black-majority neighborhoods. Many of them suffer from devaluation and protracted lack of investment and development, then when they finally do attract investment and development, it often ushers in gentrification which drives out Black residents. While this is true for renters and homeowners alike, renters are more vulnerable and usually more numerous in such neighborhoods, so they bear the brunt of gentrification’s impacts.

There ought to be a way renters can get a share of the benefit when their neighborhoods develop and property values rise, instead of getting displaced. The non-profit Trust Neighborhoods has designed one: the Mixed Income Neighborhood Trust (MINT).

Trust Neighborhoods helps local community groups in places like Tusla’s Kendall Whitier neighborhood set up MINTs to build high-quality affordable housing, not just in one project or one block, but scattered across the whole neighborhood. Using debt and equity financing, the local group builds new rental units on vacant lots, and buys and renovates vacant buildings and “naturally occurring affordable housing” (or NOAH — housing which happens to be low-cost, but which is not federally subsidized).

As the local MINT partner assembles its portfolio of rental units across the neighborhood, it does something counterintuitive with them: it rents them out at a mix of different rates. Most units are subsidized and required to stay permanently affordable, but a minority of them are allowed to have their rents rise at market rates, cross-subsidizing affordable units whose capped rents rise only at the rate of inflation.

As in the Frolic model, MINT renters are also co-owners, holding shares that give them an equity stake. But instead of holding shares in the particular project where they live, they hold shares in the entire portfolio of MINT housing across the entire neighborhood. That way, all the tenants who can afford to pay higher, market rents subsidize rents for all the tenants with lower incomes, preserving affordability.

As the MINT’s properties and the whole portfolio appreciate in value, the value of the shares goes up for everyone, subsidized and market-rate renters alike, enabling them to build wealth.

This makes renters of affordable housing economic stakeholders, creating a degree of alignment between them and homeowners. Normally, their interests diverge, since higher rents and property values benefit homeowners, but hurt renters and tend to displace them. But with MINTs, renters and homeowners alike benefit as neighborhood housing prices rice. In that sense, MINT renters are like owners.

It’s an innovative model that draws on some deep wells of experience. Trust Neighborhoods is a partner organization of the Brookings Institution. Before joining it, CEO David Kemper helped create New York City’s Division of Capital Planning, and managed affordable housing finance under the Bloomberg and de Blasio mayoral administrations. Prior to becoming Trust’s chief operating officer, Kavya Shankar worked at McKinsey and Company and the Obama White House, then helped start the Obama Foundation. They both applied the lessons of their experience to designing a system that gives renters a stake in neighborhood development, and lets them benefit from it similarly to homeowners. “Philosophically, we want residents who don’t have wealth today to invest to be able to participate in the benefits,” says Kemper.

MINTs are financed with a mix of philanthropic investments and so-called concessionary capital, which is willing to accept low returns. Equity returns are split between the funders and the neighborhood, building community wealth long-term.

“Instead of trying to raise capital from residents, the funding structure is based around harnessing the capital that wants to be in the neighborhood in a non-destructive way. We’ve actually structured the MINT so that money stays in the neighborhood,” says Kemper. “If a neighborhood appreciates dramatically in value, instead of an extractive proposition where outside investors are the ones that get all the benefit, there’s almost a soft cap on investor return. A larger and larger percentage of the returns stays in the trust as a fund for the community. There are some guardrails around how it can be spent. But the idea is, that money will become important five years out and beyond, so the fund is somewhat flexible, relying on the sense of the trustees of that future time of how it should be allocated. It could be anything from issuing a dividend for everyone in the neighborhood, to making capital improvements to community assets like lighting or sidewalks in a park.”

MINTs are structured to protect renters’ interests and give them a stake and a voice in how the neighborhood develops. Trust Neighborhoods conducts workshops to teach community members how the model works, elicit what they care about most and identify how MINTs can help them accomplish it. If renters are underrepresented in work of the local partner group, the workshops help increase their representation and sharpen the focus on the issues they want to address. With Trust Neighborhoods facilitating and providing legal expertise, community members actually write the legal agreement founding the trust.

“The resident workshops have been an incredible process,” says Kemper. “Residents really grab onto the model fast because we built the MINT model out of interviews with residents and neighborhood groups with similar experiences. They say, ‘how about this policy, we also want this policy, and this other policy.’ The residents themselves have some of the greatest expertise in these neighborhoods, and their ideas are really concrete and detailed. In an early workshop taking on some of the tensions to address in a Purpose agreement, a resident said , ‘oh, we’re going to be both the landlords and the tenants.’ Residents take up both sides and work through the tensions.”

MINTs are governed by a “perpetual purpose trust” which has a fiduciary responsibility to keep subsidized unit rents permanently affordable. The resident-owners steer the trust; they get a vote and representation in its governance, whereas outside investors don’t.

The MINT’s ability to engage residents early, tap their knowledge and leadership, and keep them engaged is one of the model’s particular strengths. “I worked in affordable housing in New York City,” says Kemper, “and the difference in the way MINTs engage a community is like night and day compared to the way it’s too often been done.”

But residents aren’t responsible for every single day-to-day decision, either. In coops and certain other models, residents make all the decisions themselves, which can sometimes engender conflict or disincentives that get in the way of an overarching, long-term mission. But the MINT’s governance combines community decision-making and guidance with professional expertise that helps it stay focused on permanent affordability and community benefits. The purpose trust has a stewardship committee composed of three community representatives together with legal, real estate, and property management professionals.

“These individuals are mission-oriented and incredibly aligned with the values of the MINT, but they run it as a real estate project, with the affordability mandate in mind,” says Kemper. “We hope that the trust stewardship committee in most cases is very bored, because the project is operating smoothly according to built-in guardrails, so it runs efficiently and also delivers real impact for the community.”

Two fully funded MINT pilots are underway: one is in the Lykins neighborhood of Kansas City; the other is in Kendall Whittier. The Kendall Whittier MINT was established by the Growing Together, a local partnership supported by the Community Action Project of Tulsa County. Growing Together realizes that downtown’s growth will stoke demand for affordable housing, and is working to stay ahead of it. Kendall Whittier has 230 empty lots, which the group can leverage as an affordable housing resource through the MINT. Its philosophy has been described as “gentrification with justice” for Kendall Whittier residents [iv].

“Gentrification is a very loaded word, but in a way, MINTs are hacking gentrification in service of current renters,” says Shankar. “We’re getting ahead of gentrification and actually using it for the benefit of renters, which is the population most vulnerable to displacement.”

– Kavya Shankar, COO, Trust Neighborhoods

The MINT model, though still being tested, is designed for scale. MINTs don’t just create one affordable housing project, or even a whole block at a time, but a whole portfolio of housing that can help steer the direction of the whole neighborhood. And they’re attracting interest from neighborhoods nationwide.

At present writing, Trust Neighborhoods has 126 local community development organizations in its pipeline eager to explore MINTs , including in Oakland, Cleveland, Memphis, and Atlanta. In the short term, Trust is fundraising to staff up and hopes to support five of these neighborhood organizations to start their own MINTs later this year.

Grounded Solutions, the organization that assists and networks hundreds of community land trusts nationwide, sees MINTs as complementary to CLTs, and has expressed interest in offering them to its members. Trust Neighborhoods anticipated growing demand and uptake as it set up the Kansas City and Tulsa pilots, deliberately developing legal documents and other features that can be used as templates to streamline the creation of new MINTs.

“The idea was every step of the way, build something that could be taken to another neighborhood and used in that context,” says Shankar. “So we spent a lot of time upfront on the process, but I think will pay off as we start to move into other neighborhoods. There are a lot of community development solutions that are really incredible, but their scope is very small. We want MINTs to be a standard affordable housing product that is recognizable, replicable in many neighborhoods, trustworthy for the community and investors, and able to put private capital to work in service of neighborhoods.”

Whereas community land trusts are attracting public investment and becoming widespread, for now, Trust Neighborhoods, Frolic, and Parity remain small-scale but powerful examples of innovations that have the potential to catch on and shift markets toward equity and community.

All four models each change basic parts of the traditional housing equation. CLTs replace fee-simple ownership with owning the home and leasing the land from a community-led trust, creating permanently affordable housing. Parity replaces atomized individual buyers with a group of buyers who are already socially connected and bring their own social capital with them, instantly creating connected neighborhoods a block at a time. Frolic replaces single-family properties in upzoned neighborhoods with multi-family coops which build community, fight displacement, and allow generational renters to enter into homeownership. Trust Neighborhoods replaces high market rents that force people of limited income out of gentrifying areas with a structure that makes renters co-owners, keeps their rents below market, and allows them to benefit from the neighborhood’s appreciation in value.

Each of these models are examples of how fundamental aspects of the housing market can be consciously redesigned for equity, inclusion, and community, and how market redesign has the potential to solve retrenched problems. They illustrate, each in their own way, how it’s possible to unwind devaluation of Black neighborhoods and its downstream consequences, and re-value Black communities, if the structural roots of these problems are addressed with structural solutions.

endnotes

[i] https://tulsaworld.com/business/local/tulsas-housing-market-from-the-subprime-mortgage-crisis-to-global-pandemic/article_654ec546-f08a-11eb-ae2a-07f7de312a2b.html

[ii] https://www.vox.com/2015/4/28/8507493/baltimore-riots-poverty-unemployment

[iii] https://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/40119/187138025-MIT.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

Acknowledgements

The Economic Architecture Project would like to thank the anonymous funder for generous support.

The authors would like to thank Rara Reines, Steve Kent, Lael Cox, Jasmyne Jackson, Elmo Tumbokon, and Sulaiman Yamin for dedicated work that made this paper possible.

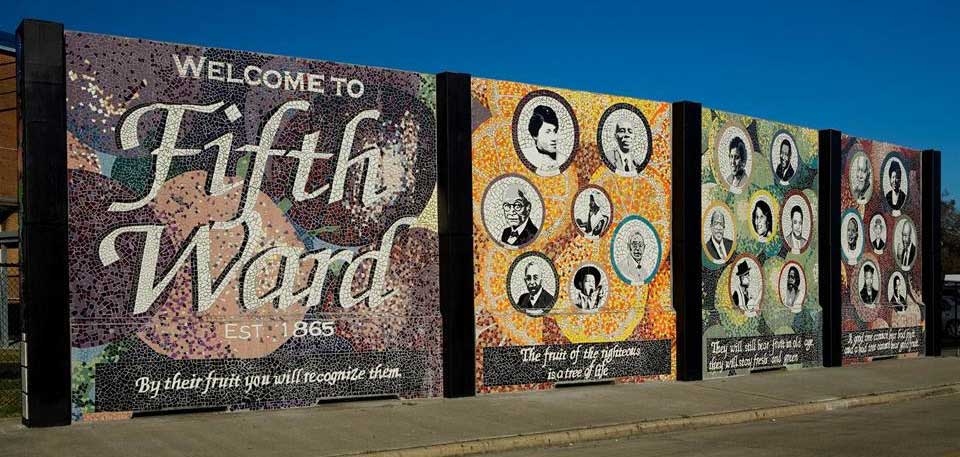

Mural Title: “Midtown Square Mural”

Designed and painted by: Takiyah Ward

Photo provided by: Lake Union Partners

Design & Layout: JC Ospino / Alliter CCG