Download this article as PDF here.

How CLT innovators are pioneering structural changes in housing markets.

Longstanding discriminatory practices have led to devaluation of homes in Black-majority neighborhoods, making them targets for real estate speculation and leaving them vulnerable to forms of development that increasingly displace Black residents.

In addition, economic shocks resulting from sudden, unpredictable events like hurricanes or pandemics disproportionately impact Black communities and can also can cause rapid displacement. This is another aspect of a broad pattern of racism and environmental and economic injustice.

But it’s important to recognize that displacement isn’t primarily caused by sudden disruptions, though they can trigger it or make it worse. Whether in good times or bad, Black people are vulnerable to displacement due to longstanding, man-made, structural conditions in our markets and public policies. They require fundamental, structural solutions.

In search of such solutions, some community groups are experimenting with community land trusts (CLTs). CLTs fundamentally change the structure of homeownership by separating the value of the home from the value of the land it sits on. Homebuyers pay the price of the house alone, while ownership of the land is retained by a community-led trust. This takes the value of the land and its appreciation out of the equation, permanently lowering the price of the home and disincentivizing the kind of speculative development that leads to gentrification and displacement. CLT ownership is designed to provide housing security, maintain affordability, enable residents to stay in the home as long as they want, and preserve community and cohesiveness in the neighborhood.

To date CLTs have mainly been used to develop owner-occupied residential housing. But as gentrification and displacement pressures mount, and as communities seek to recover from pandemic-induced disruptions, CLTs are attracting growing interest, and the CLT structure is getting adapted and applied in new ways. For example, it’s now used to establish secure rental housing, champion tenants’ rights, convert existing homes to affordable housing, or develop affordable commercial properties, green spaces, and multifamily housing. CLT growth and adaptations are also starting to generate market and policy shifts, such as changes in state property tax law to accommodate them, or new products for banks, governments, and government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) to fund them.

There only about 10,000 CLT units nationwide – a tiny number compared to overall affordable housing inventory, which includes 7.3 million rental units [i]. Existing CLTs meet only about 1% of the estimated need for them, so there both need and potential for them to scale up. Some trusts applying the CLT model in new ways have just a handful of units in their portfolios. But the power of their innovations isn’t limited to the number of units they create. It’s also in how they make structural changes to market conditions, which may have far-reaching impacts.

CLTs are evolving alternative ways for affordable properties to be bought, sold, assessed, taxed, financed, and managed for the benefit of residents and communities. Those sorts of structural changes to the housing market could be key to unwinding elements of structural racism embedded in them today, including the structures that drive displacement of Black residents.

From devaluation to displacement

Black neighborhoods are often subject to a destructive cycle of devaluation, disinvestment, and displacement. Longstanding discriminatory practices, from explicit exclusion by restrictive covenants, to effective exclusion through redlining, often kept prospective Black homeowners from buying into all but a relatively few designated areas. At the same time, discriminatory practices also devalued Black-owned assets in areas where they were able to buy.

Today, homes in majority Black neighborhoods are devalued by an average of 23% (worth on average $48,000 less per home, or $156 billion less collectively) relative to comparable homes in neighborhoods with very few or no Black residents.

Home prices in Black- majority neighborhoods don’t reflect their real value, and are much lower than otherwise comparable homes in white neighborhoods. Nor do property values in Black neighborhoods reflect neighborhood social capital which Black residents have built up over time.

Devaluing Black assets deprives Black homeowners of wealth, making them more vulnerable to displacement. It also undermines neighborhood growth and leads decline and disinvestment as banks and investors go elsewhere, local businesses close, and new ones don’t open. Property values fall, and when they reach a certain threshold, outside investors scoop up devalued assets and develop them in a way that maximizes their own returns, driving up real estate prices. That forces established businesses and long-term residents out, ultimately destroying Black communities that took generations to build.

It’s an all-too-familiar cycle in cities throughout the U.S. For example, median home values in Black majority neighborhoods in the Houston area are $54,000 (27.6%) lower than comparable homes in white neighborhoods. Despite its booming housing market, with the net population is growing by 250 people every day, Houston is increasingly losing Black residents, including thousands who have been forced out of important historically Black neighborhoods.

Compared to white neighborhoods, median home values in Black neighborhoods New Orleans are depressed by nearly $46,000, or 20.8%. In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, higher- income-oriented redevelopment reshaped Black neighborhoods, proving so damaging to them it was likened to “ethnic cleansing.” A third of Black residents were displaced. Today, the population in key historically Black neighborhoods is only about half of what it was before Katrina.

A short CLT primer

Originally, community land trusts were designed to enable Black land ownership and land-based livelihoods.

The first one was established in rural Lee County, Georgia in 1969 by New Communities Inc. to help Black famers overcome forces excluding them from owning land such as industrial farming, racial discrimination, and predatory lending.

Through the 1970s, most CLTs were designed to help Black farmers buy rural land. Starting in the 1980s, the CLT model was adapted to make urban homes affordable amid growing gentrification. Urban CLTs proliferated during the housing boom of the 1990s.

CLTs are based on an alternative conception of property rights and homeownership. The standard form of property ownership in the US is fee-simple ownership, where the buyer becomes the owner of the house, the land, the production rights, etc. Instead, CLTs are based on the English leasehold model in which the buyer becomes the owner of the building, but not the land. The trust retains the deed to the land, which the buyer leases. This lowers the purchase price and carrying costs of the house.

In ordinary fee-simple homeownership, land is a store of wealth. It is finite and scarce, so it appreciates rapidly, continually driving up property values and prices over time. This is what makes traditional homeownership a vehicle for speculation, and allows for those with sufficient capital and credit access to make large profits and build wealth by buying housing cheap and selling it dear.

Housing is the only basic human necessity we treat as a vehicle for speculation, using it to build wealth for privileged groups. Imagine what would happen if we treated other basic necessities like food or water the same way, concentrating them in wealthier hands, driving up prices. It would result in price gouging, hoarding, and shortages. We’d reject that as unethical and unacceptable. But since all people need shelter, just as they need food and water, why should driving up housing prices to build wealth for speculators be any more acceptable?

CLTs represent a structural shift in homeownership that precludes using housing in this way. Instead of buying and reselling homes to make a profit, CLTs keep them affordable and enable residents to stay in them long-term. Most community land trusts are non-profit organizations governed by residents, community members and public representatives. CLT leases are long (typically 99 years) and can be inherited by the owner’s heirs or designees. The owners have responsibility for maintaining the house and can improve it as they see fit.

In that sense CLTs offer the same kind of housing security and self-determination as fee-simple ownership. But because the buyer leases the land instead of owning it, the house can be purchased for much less, often as low as a third of market price. The land trust raises or finances the money to make up the difference between the sale price and the market price, subsidizing the initial purchase and enabling people with limited income to buy the home.

In exchange for that opportunity, buyers accept a limit on how much equity they can build, since the appreciation of their property is tied to the value of the house itself and excludes the rising value of the lot it sits on. For CLT homeowners, appreciation might be capped at 1% or 2% of the base price annually. While that severely limits homeowners’ upside, it has one crucial benefit: it also limits how much the market value of the house can rise off the base price, keeping the house affordable far into the future.

In the CLT model, an owner can build at least some equity, though the house is no longer a store of wealth and a vehicle for speculation. It can’t be bought and flipped for a big profit, for example. Even if other housing prices in the area skyrocket, the price of a CLT home will stay low, no matter how many times it is sold. This helps keep neighborhoods stable and affordable and helps protect residents from being displaced.

At the same time, the pooled resources and inclusive governance structures of the land trust give community members control over how the trust’s assets are managed, and as the trust’s portfolio grows, they can influence how their own neighborhood develops.

In addition to their inherent advantages, CLTs also have disadvantages that make them difficult to scale. For example, they are capital-intensive, and there’s a mismatch between available funding vs. what would be required for CLTs to meet more of the need. In fact, some analysts argue that because they’re chronically under- resourced, community land trusts may actually perpetuate an artificial scarcity of affordable housing in Black neighborhoods, whereas wealthy neighborhoods have all the development resources they need.

Real estate transactions happen relatively fast, and it’s often difficult for CLTs to assemble financing and move fast enough to take advantage of buying opportunities. Since CLTs are managed by community members, not real estate professionals, there’s a steep learning curve to climb, and a need for outside expertise that not every community-based organization can access readily. And although they are designed to help counteract structural racism in housing markets, CLTs in marginalized communities can still be subject to it themselves, encountering explicit or implicit discrimination and exclusion when they try to obtain the assets, funding, financing, or expertise they need to succeed.

At the same time, CLTs are proving versatile and fertile ground for innovation, and they are evolving solutions to these problems. Some innovations described below are designed to attract more financing, facilitate mortgage lending, or broaden the scope of community-led development, while growing CLT networks are building and sharing expertise. It’s a complex ecosystem. There are hundreds of CLTs nationwide, and a large body of work which studies and explains them in detail. Resources for exploring them further include the Grounded Solutions Network (profiled below), Shelterforce magazine, and the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and its Community Land Trust Reader.

Four Houston neighborhoods dealing with displacement

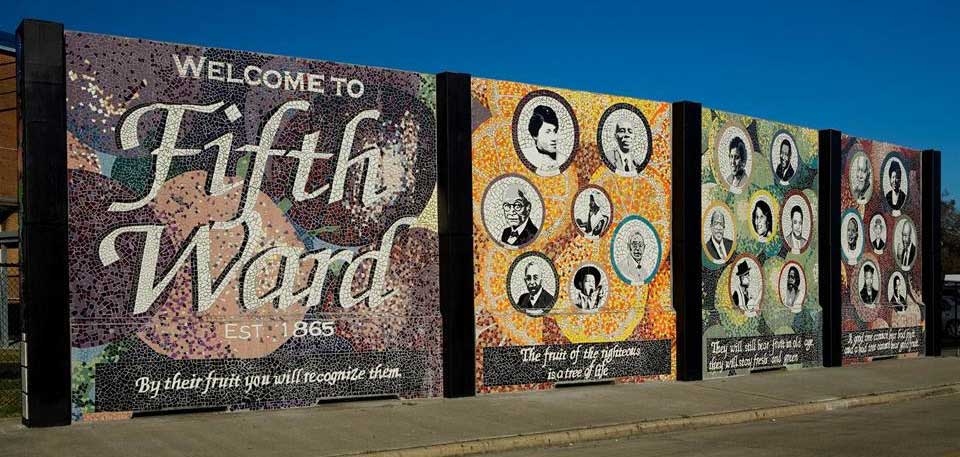

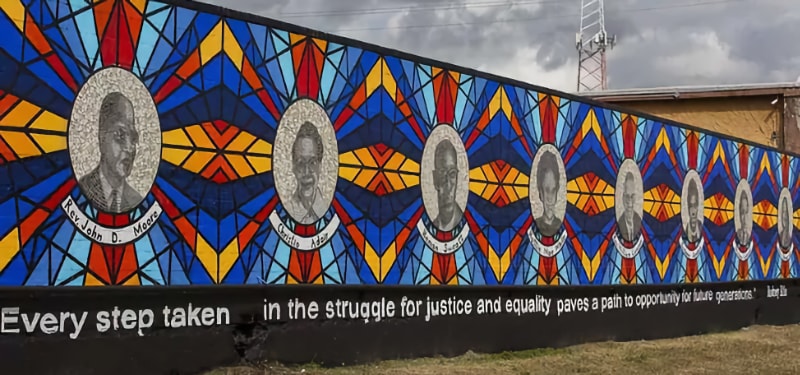

Displacement pressures are especially strong in formerly affordable, historically Black Houston neighborhoods and suburbs inside Beltway 8 – neighborhoods like the Third Ward, the Fifth Ward, Sunnyside, Independence Heights, all of which are now gentrifying.

The Third and Fifth wards prospered in the 1920s, as successful Black business owners and civic leaders built outward from the stronghold of the Fourth Ward, which was known as Freedman’s Town. It was Houston’s first Black neighborhood, established soon after Emancipation. Just outside the city, Independence Heights, the first Black city in Texas, was chartered in 1905. Sunnyside followed seven years later. They both grew into thriving Black-majority communities with businesses, schools, and infrastructure. Both were later annexed by Houston.

Today Black residents are increasingly getting forced out of these communities. The Third and Fifth Wards, Sunnyside and Independence Heights lost some 10,000 Black residents from 2000 to 2018. Homeownership rates in those neighborhoods are falling while the share of rentals is growing, which is associated with high turnover and weakened community ties. Most housing in the four neighborhoods is rental housing; in fact, in the Third Ward, 75% is rental housing.

Median income in the four neighborhoods is low – about half of the median income in Harris County generally — and it’s declining in three of them. Meanwhile rents rose by more than 5% over the past year. According to a study by the Kinder Institute at Rice University, a majority of renters in Houston and Harris County are cost burdened, meaning they spend more than 30% of their income on rent, straining their incomes, and leaving them vulnerable, perhaps one disruption away from displacement.

Many of Houston’s Black residents were in that position when Hurricane Harvey hit in 2018, when the pandemic hit in 2020, when the Big Freeze left thousands in Houston without power in February 2021, when the utility shutoff moratorium ended in June, and when the eviction moratorium ended in September.

“If one thing, one emergency, happens, you’re going right underneath that water,” said Kendra London. She, her grandmother, her mother, and her children grew up in the Fifth Ward, but she was forced out in 2019 due to rising rents that took more than a half of her paycheck after taxes and medical expenses. Now she’s an advocate for building more affordable housing in the Fifth Ward so displaced residents can move back.

But affordable housing is in increasingly high demand and short supply. Unlike other gentrifying neighborhoods in Houston which have added thousands of new units in recent years, the Third and Fifth Wards, Sunnyside, and Independence Heights have seen little new construction, causing their median home prices to skyrocket, and leaving residents who rent with few options for buying homes in those neighborhoods. Tax assessments are rising along with home prices, which also puts current homeowners at risk for displacement.

“Communities of color inside Houston’s 610 loop or even inside Beltway 8 are now hot spots everybody wants to develop, because land is cheap, and they’re centrally located,” said Ashley Allen, CEO of Houston Community Land Trust. “When people moved to the suburbs, these areas were disinvested, nobody thought about them. Now people are moving back to the city, which we’ve seen happen in a lot of metro areas. Developers are buying cheap blocks and putting half-million-dollar townhomes on them. They try to put as many units on them as possible to create higher density, which doesn’t match the landscape of what Houston is. There’s nothing to protect the senior who’s been in the community for 50 or 60 years. Her land is now worth $300,000 and she is going to get taxed accordingly.”

On land abutting the Third Ward, Rice University is developing 16 acres of commercial, residential, and vacant property to create the South Main Innovation District. It includes building an incubator space in the old 270,000-square foot Sears building. But that could exacerbate the pressures driving Third Ward Black residents out, and the plan has drawn opposition from the Houston Coalition for Equitable Development without Displacement. HCEDD is campaigning for Rice Management Company to sign a community benefits agreement to support Black-owned business development and partner with the Houston Community Land Trust to build 1,000 new affordable housing units in the Third Ward.

Innovating CLTs in Houston

Houston is among the fastest-growing metro areas in the country, and despite its reputation for affordability, it’s also one of the places where Black residents are hardest pressed by gentrification, and at highest risk for displacement, even from communities founded and built by Black residents.

Last year, the net population of the Houston metro area grew by 250 people[ii] every day, as people flocked to the area seeking job opportunity and affordable neighborhoods. But from March 2020 to March 2021, home prices grew 16%[iii], pricing many Houstonians of limited income out of the market.

“Everybody has this idea of Houston being super affordable,” says Ashley Allen, CEO of Houston Community Land Trust (HCLT), one of the fastest growing CLTs in the country. “People think if you move to Texas, you automatically get a huge house with a huge yard as soon as you get here. The reality is that those houses in once affordable communities are no longer affordable. People are going to be displaced.”

Community leaders in Houston’s Black neighborhoods such as the Third Ward and Independence Heights had known for decades that because of their central location they would eventually become targets for gentrification. In fact, at various times they had proposed community land trusts as a way to counter anticipated displacement pressures.

But by the time the current mayoral administration took office in 2017, gentrification of Houston’s Black neighborhoods wasn’t just feared, it was well underway, and those communities were increasingly losing Black residents. In 2018, the City established the Houston Community Land Trust (HCLT), which partners with the Houston Land Bank to build quality, affordable single-family homes on City- owned lots. Newly built three-bedroom homes in the program start at just $75,000.

The homes are purchased with 30-year fixed mortgages. HCLT works with community partners that provide homebuyer education programs, and can help prospective buyers who need to raise their credit score to 620 or better to qualify for a loan. But as Allen is quick to point out, the widely held notion that lack of education or financial literacy is what prevents Black people from owning homes is a fallacy that serves to justify and perpetuate low rates of Black homeownership.

“In a lot of programs, the buyers would do the work, go to the homebuyer education classes, and get their credit together,” Allen says. “They get super excited, save up their down payment, then they go to a bank and they’re only approved for $100,000 when there are no homes in that price range. So they get discouraged. They think, ‘Why did I take this class? Why did I save this money? I did the right thing, I go to work every day. But I still can’t buy a home.’”

The mismatch between available loans and available homes is an obstacle to homeownership which is baked into mortgage and housing markets. While homebuyer education programs are important, they do nothing to address this structural problem, which can’t be blamed on buyers’ lack of financial literacy.

That’s why HCLT also conducts lender education, working with banks to help them understand how underwriting CLT mortgages is in their interest. In fact, they are lower-risk than traditional fee-simple mortgages. CLT purchase prices and monthly payments are below market, so loan principals and default risks are lower. HCLT also builds in foreclosure prevention measures, such as a right of first refusal for the trust to step in and assume the loan in the unlikely event of a default.

The approach has proven effective at mitigating the disconnect between available loans and available affordable homes. Working with both banks and buyers, today HCLT has helped 62 applicants obtain mortgages and purchase a home, scoring a much higher success rate for qualifying than most other affordable housing programs. This is one example of a data point indicating CLTs are addressing a structural problem, in this case the obstacles to Black homebuyers qualifying for loans, and beginning to move the needle away from the status quo toward solutions.

Another structural problem is the limited reach of many CLT programs, since they can only build so many units, often concentrated in a specific area. Typically, it’s the units themselves which attract prospective buyers to CLT programs. For example, under its New Home Development Program, HCLT acquires lots owned by the Houston Land Bank in gentrifying neighborhoods like the Third and Fifth Ward, Sunnyside, and Independence Heights, and builds affordable units on them, which then brings homebuyers to the Trust to inquire about buying them. But an alternative HCLT program called Homebuyer Choice flips that equation. It lets homebuyers with limited income find a home they like in any neighborhood, initiate the purchase, then bring the Trust in to complete the transaction. Such “buyer-initiated purchases” are a further evolution in the CLT model that could help overcome its limitations.

Buyers in the program can choose any home anywhere in the Houston metro area, and as long as it meets certain criteria, HCLT will subsidize the purchase with up to $150,000. Once the owner buys it, the home becomes a permanent part of the Trust, whose mission is to keep it secure and affordable. That way, the Trust’s holdings aren’t limited to City-owned land in certain neighborhoods; they can expand throughout the metro area, and HCLT’s affordable housing portfolio can grow rapidly. Typically, it takes three years from incorporation for a CLT to achieve its first home sale. Now entering its third year, HCLT has 62 homeowners as of the end of 2021, and is on track to grow its portfolio to 150 homes by mid 2022.

“A lot of CLTs just build their own homes,” Allen says. “We don’t have that luxury here because the market is moving so fast. We also have to use the homes that are already available on the market. What’s helping us get more homes quickly is subsidizing what’s already there.”

Critics may argue that a Homebuyer Choice subsidy of up to $150,000 is an expensive proposition for one home, but Allen says, “it’s not if you know you never have to put more [subsidy] money back into that property again. In other programs, families may get $30,000 or $40,000 in subsidies to buy a home, then in 10 or 20 years they can sell it at market rate, and it’s no longer affordable. At that point, you’ve just lost your $40,000 investment.”

Allen is referring to Houston’s earlier Homebuyer Assistance Program, which predates HCLT. It gives homebuyers a one-time subsidy up to $40,000, but since housing prices are rising so fast, in many cases that $40,000 subsidy won’t bring the cost of a home down enough for limited income buyers to afford it. And since the subsidy doesn’t do anything to change the underlying market structures driving prices up, subsidized properties can be resold at market rates, so whatever degree of affordability the subsidy confers may not last long.

The Homebuyer Choice program on the hand offers more than just a bigger subsidy; it offers a different form of ownership that keeps the home secure and affordable permanently.

That not only helps lower home prices and barriers to homeownership for Black buyers, it also helps fight housing shortages driven by price distortions. HCLT limits appreciation of the home to 1.25% annually, which removes the incentive for speculation. In addition to that modest upside, keeping homes affordable also helps homeowners build wealth in other, positive ways.

“People are able to live comfortably because they’re not paying more than 30% of their income on housing costs,” Allen says. “They are able to put their extra money into other forms of wealth building, put more into 401ks and college funds, and pay off medical bills and student loans. If you’re looking to make money off your home, if you’re using it as your main wealth building tool, this is not the program for you. But if you’re looking for affordability so that you can build your credit and have more space to create wealth, then this is for you.”

HCLT is working on ways to apply the same principles to commercial real estate, green spaces, and eventually, multifamily housing. “We need affordable rentals, since not everybody is ready to buy and not everybody wants the responsibility of homeownership,” Allen says. “We want to make sure that there’s affordability for those people, too, and multifamily may be another way to do that.”

The City of Houston recently floated $52 million in bond funding to help HCLT finance sales of 400 affordable units by 2023 — the biggest public financing of CLTs to date. This year HCLT will kick off a campaign to raise another $88 million to reach 1000 homes in the next six to seven years. That’s an ambitious goal, but it’s still only about 5% of Houston’s estimated need, which is at least 20,000 homes.

Meanwhile, growing recognition of CLTs’ potential in Houston is also prompting policy shifts that have important ramifications in their own right. The Texas State Legislature passed a bill which just took effect, expanding the types of organizations that can establish CLTs in the state, and changing tax assessment rules so that CLT homes are assessed only on the basis of the subsidized purchase price and ground lease, not the market value of the property. That will lower taxes for CLT homeowners and support faster development of community land trusts in the state.

Prior to the change, Texas policy was in a sense aligned with real estate speculation, which drives up property values, property taxes and tax revenues. When higher property values result in higher taxes it pushes residents out of neighborhoods. The rising property values attract more speculative development and gentrification, which undermines affordable housing, housing security and Black homeownership, extracts value from Black neighborhoods, and drives displacement. But by taxing CLTs on a different basis from fee-simple ownership and real estate speculation, the State is shifting its policy and revenues to align with a more just, sustainable alternative. It recognizes that CLT properties don’t appreciate the way other properties do, and the reduced tax burden alleviates one of the most significant displacement pressures. More public investment and legislation supporting CLTs in Houston and Texas are in the works.

Houston Community Land Trust doesn’t operate at the scale of the need for affordable, secure housing, even though it is one of the nation’s largest CLTs. Even with substantial City funding and a major capital campaign, its current goal is to meet just 5% of local affordable housing needs. Other community development NGOs are generally much less well-resourced than HCLT, and scaling up the nonprofit sector as a whole to meet the need is a challenging proposition.

Yet there are other forms of impact besides scale itself. Structural innovations like the ones HCLT has introduced, such as working with banks, buyer-initiated purchases, or changing state policies, are powerful because they help create new market conditions for wider uptake of CLTs, shifting market structures and policies away from speculation and displacement, towards housing security, affordability and equity. They also demonstrate the ability to quickly and effectively put a large and growing amount of capital to work to address displacement. While HCLT and other innovative CLTs continue to face challenges and limitations in terms of reaching scale, they’re also continuing to evolve new ways of addressing them.

Structural inequities in New Orleans

Houston’s population is booming, but New Orleans’ is shrinking. Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005 and disproportionately affected Black residents, driving a third of them out of the city.

They were three times as likely as white residents to be flooded out in the storm, since historic discriminatory housing and lending practices concentrated higher ground property in the hands of white homeowners. By the time banks started lending to Black buyers, what was left was mostly flood-prone property.

In 2015, a decade after Katrina, as New Orleans celebrated its resurgence, the Black population was still almost 100,000 lower than before the storm.

Majority Black neighborhoods like the Seventh Ward, the Lower Ninth Ward, and Pontchartrain Park remained largely unrebuilt and unrecovered. As of 2019, Black residents make up 61% of people in New Orleans without housing.

Before Katrina, the city had thousands of affordable units in housing projects known as the “Big Four.” They were mostly undamaged by the storm, yet the City bulldozed them anyway, part of civic leaders’ avowed policy to rebuild New Orleans as a wealthier, whiter city. U.S. Representative from Massachusetts Barney Frank said that it amounted to “ethnic cleansing.”

The Road Home, the largest housing recovery program in U.S. history, disbursed $13 billion in federal aid to New Orleans homeowners, apportioned according to the appraised value of the home rather than the cost of rebuilding. Since housing in white neighborhoods was appraised far higher than comparable housing in Black neighborhoods, white neighborhoods netted the majority of Road Home funding. In 2010, a federal judge ruled the program was racially discriminatory. But by then more than 98% of the money had already been spent.

“It took us almost ten years after Katrina to be able to assess and address the core needs and structural inequities in New Orleans,” said Andreanicia Morris, Executive Director of HousingNOLA, a partnership between the City and public, private, and nonprofit organizations working to solve New Orleans’ affordable housing crisis. “Katrina relief money flowed into the city with no control for basic racial inequities. That’s why it failed. A number of systems failed because of racial inequity, from investments in our levee system to helping those who were stranded in their homes. This is all rooted in the deepest problems that News Orleans and the United States have had for centuries. We watched as programs were created that reinforced systemic inequities and didn’t control for them.”

In recent years, new disruptions, including Hurricane Ida and the covid-19 pandemic, compounded by low wages and high housing costs, have left Black residents with fewer options for staying in or returning to the city, and more are getting forced out. They still constitute a majority of New Orleans residents — nearly 60%. But discriminatory lending practices, real estate speculation, gentrification, predatory tax sales, substandard housing conditions, and a lack of legal protections for tenants have made the city increasingly difficult for people of color to live in. An estimated 33,000 new affordable housing units will be needed in the next ten years to combat these trends.

Many of those will have to be rental units. Since 2000, rents in the city rose 50% and home prices 54%, while incomes rose just 2%. Wages are low, work is often temporary or seasonal, for example in the tourism and fishing industries, or intermittent, such as Uber or childcare gigs. Jobs in tourism, hospitality, and restaurants were disrupted by the pandemic and have been slow to return. But the pandemic didn’t depress home prices, which climbed 9.5% over the past year.

As a result, the New Orleans has become unaffordable for many Black residents, and the need to create decent, affordable rental units is urgent. Most New Orleans renters are cost- burdened. 61% spend more than a third of their income on rent and utilities. 38% spend more than half their income on housing, a red-flag indicator in which New Orleans ranks second in the nation. Black residents make up four out of five of cost-burdened New Orleans renters. About 28,000 people are on the waiting list for Section 8 housing in the city. 78% of rental properties require major repairs for leaks, infestations, plumbing, mold, and other problems.

Championing affordable rentals and tenants’ rights in New Orleans

Black residents of New Orleans experienced massive displacement from Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath. Redevelopment intentionally made New Orleans a richer, whiter city.

Today, new disruptions such as the pandemic, growing gentrification, and the rise of tech- enabled short-term rentals for tourists are ratcheting up displacement pressures. Available housing inventory is down to its lowest level in a decade, public housing is now rented out at market rates, and affordable rentals are disappearing.

“As New Orleans grows and prospers, rents go up, and the folks who need to live in the city, or the folks who work in the city can’t to afford to live here,” said Veronica Reed, executive director of Jane Place Neighborhood Sustainability Initiative. Jane Place is a small community land trust and housing justice organization in New Orleans’ Black-majority Mid-City neighborhood, where 55% of the residents are Black, and 33% live below the poverty line.

Displacement risks for renters in have been exacerbated by the recent proliferation of short- term rentals (STRs) catering to tourists via online platforms like Airbnb and HomeAway. Over 6,000 homes and counting in New Orleans are STRs. As neighborhoods becomes more transient, their community character and social capital erode. And as more homes are reserved for tourists instead of residents, turnover rates rise, driving up rents and home prices. That forces more Black residents out, with STR owners profiting from their displacement. “Our neighborhoods surrounding downtown were basically becoming ghost towns, with blocks and blocks of housing only occupied Thursday through Monday morning,” Reed says.

“Those who can’t pay the higher rents in the city end up living in surrounding parishes. But they have the added expense of transportation. There is limited regional public transit, so that means they have the cost of a car and insurance. And then they have the cost of parking downtown. So, they’re going to pay one way or the other.”

Jane Place issued a report documenting widespread abuses and illegalities in the STR sector, exposing the pernicious effects of STR proliferation on Black renters and neighborhoods.[iv] Together with Loyola University’s New Orleans College of Law, it published research drawing a direct connection between STRs and eviction rates.[v] That laid the groundwork for changing the laws governing STRs.

Under a 2016 City ordinance, in theory some of the licensing and other fees STR owners paid were supposed to go toward affordable housing. But in practice, those revenues only added up to the cost of establishing a single unit of affordable housing. That effectively ignored STRs’ negative impact on renters and neighborhoods like Mid-City. But in 2019, the City passed two new ordinances advocates hope will discourage STR proliferation. The first requires STRs in residential neighborhoods to have a homestead exemption, making whole home rentals owned by investors and speculators illegal. The second new ordinance established a new structure for permits and fees, operating ordinances, and enforcement penalties. Jane Place is monitoring the impacts of the new laws on STR licenses now and plans to issue a report on it in early 2022.

“The new regulations went into effect right before the pandemic hit, in December 2019,” Reed explained, “then the bottom fell out of the short-term rental market. A lot of STR owners quickly moved back into the long-term market. Now we have observed instances where landlords are trying to force these tenants out to return the units to the short-term rental market. That is a factor in a number of eviction filings we’re seeing right now through our Early Eviction Warning System and Eviction Court Monitoring.”

New Orleans is one of the most difficult markets for secure housing. It’s a Black-majority city so rich in social and cultural capital that it attracts visitors from around the world, yet its Black- majority neighborhoods are devalued. In the wake of Katrina, $13 billion in “Road Home” federal aid was allocated according to appraised value of housing before the storm, and since Black- majority neighborhoods are chronically under- appraised, most of that money bypassed Black homeowners. As a result, Black neighborhoods were slow to rebuild, and Black residents either didn’t return or were forced out as gentrification and tourism resurged.

Those who remained were largely renters, including 79% of Mid-City residents today. After Katrina, federal rental assistance was offered, but it was temporary, lasting on average 15 months. Such aid is intended to “facilitate disaster-affected households’ transition back to permanent, market-rate housing.”[vi]

But for many Black residents, transitioning to permanent market-rate housing is precisely what’s forcing them out of New Orleans. What kind of intervention could enable them to stay, offer them secure rental housing, and create and preserve sustainable, economically just neighborhoods and communities?

Answering that question is Jane Place’s mission. It started as a community collective which purchased three-story, 11,000 square foot warehouse in the mixed New Orleans neighborhood of Mid-City in 2005. The intention was to convert it to a limited-equity housing cooperative, with some collective space for community-based projects. Then Katrina hit two months later, and the group shifted its focus to recovery and rebuilding. It officially incorporated as the Jane Place Neighborhood Sustainability Initiative in 2008.

Today it functions as a traditional neighborhood CLT, developing secure, affordable housing in Mid-City, with the community trust owning and leasing the land. But instead of leasing it to homebuyers, it uses the CLT structure to create affordable rentals. For example, its three-bedroom, one-bathroom units rent for just over 60% of market prices ($925 as opposed to $1500+ a month).

Jane Place’s units are subsidized through the HUD HOME Program, and are exempt from property taxes. But If such subsidies were the only mechanism they used to keep rents low, neither affordability not housing security would last long. Appreciation of the land and the buildings would eventually mount so high that market pressure would become irresistible, and either force rents up, or force owners to sell the building at a market price. But since their CLT structure shields the rental units from those pressures. The trust retains ownership of the land, preventing the sale of the property due to outside market pressures. So the units appreciate only slowly, rents stay permanently affordable and secure.

Jane Place has been innovative in finding a way to extend to renters many of the same advantages traditional CLTs offer homebuyers: security, affordability, and a chance to build modest equity.

Jane Place’s board of directors, which includes two of its tenant members, offers residents rental assistance funded out of the trust, and a savings incentive program where J.P. Morgan Chase provides matching funds to double tenant savings, up to $50 a month. It also gives tenants the opportunity to do in-kind work in exchange for payment or a break on the rent. “It’s like sweat equity attached to rent,” says Reed. “You could clean the laundry room, sweep the halls, cut the grass or attend a board of directors or committee meeting and at the end of the year, that will translate into a dollar amount. It can either be taken off December rent, or we can write you a check.”

As a result, Jane Place has very low tenant turnover, even during the pandemic — proof that even under extremely adverse conditions, it’s possible to create affordable, secure rental housing that works for tenants.

Jane Place has created 12 affordable rental units so far, with another 14-16 planned for 2022-2023. That is a small number compared to the estimated 33,000 affordable rental units New Orleans needs in the next ten years. But Jane Place’s impact is broader than its own small scale. It is demonstrating structural innovations that could potentially change rental markets and offer secure housing by creating permanently affordable units, protecting renters from displacement, and giving them a measure of financial security.

“For most CLTs, homeownership is a much easier way to go — you build it, you turn it over, you maintain the relationship but it’s on to the next house,” Reed says. “Stewardship and property management isn’t easy but I do love the relationship we have with our tenant members.”

At the same time, Jane Place is also advocating for stronger tenants’ rights policies, which could be another form of far-reaching change, including establishing the right to counsel, which could shift the pattern of rising evictions in New Orleans. Closely monitoring eviction court, Jane Place discovered two salient facts: 1). the majority of those who end up there are Black women; and 2). the controlling factor for being able to stave off eviction was having a lawyer.

“The best outcomes for tenants occur when they are represented by counsel,” Reed says. “Southeast Louisiana Legal Services can only represent a narrow group of tenants. Everyone else is on their own unless they can afford a lawyer. Most folks cannot. We estimate it would cost about $1.5-2 million a year to have everyone represented by counsel in eviction court. That’s a remarkably small price to pay.”

Jane Place and other advocates demanded this funding be allocated.[vii] The New Orleans City Council heard them and approved $2 million in the City’s 2022 budget for tenant legal representation.[viii] That effectively guarantees the right to council in eviction court.

Reed and housing advocates across the state would like a “renters’ bill of rights” enacted as state law. “There are virtually no tenants’ rights in the state of Louisiana,” she said. “The basic landlord-tenant laws were codified in the 1870s, so you can imagine there is nothing much there. Every time there’s an attempt to do something about it at the local level, maybe in a small city, it’s blocked at the State Legislature level. So in coordination with a few partners across Louisiana, we’re working on a renters’ bill of rights the state could adopt. We are also looking at a rental registry in New Orleans.”

Such policy shifts, coupled with innovations Jane Place has modeled for its own tenants, could be transformative for rental markets like New Orleans. Jane Place is a small organization and replicating and scaling its approach would require much more capital than it has access to now. But it demonstrates a powerful vision of how New Orleans could develop if we shifted investment priorities.

Jane Place responded to the same disruption (Katrina) in the same time frame as the Road Home program, but with very different priorities and outcomes. The Road Home put $13 billion behind the goal of transitioning to permanent, market-rate housing. The effects of that choice included fueling speculative development, tearing down affordable housing, aggravating inequities, displacing an enormous number Black residents, and deracinating Black communities. What if that money were invested instead in Jane Place’s goals of creating secure, affordable rentals and fighting displacement? What if it were coupled with policies aimed at curbing STRs and protecting tenants’ rights? New Orleans would be an utterly different city.

There’s nothing inevitable or pre-ordained about how New Orleans’ redevelopment played out, or how it will develop in the future. It’s a choice, a question of what those with the resources decide to invest in, and what the housing market is designed to incentivize. Jane Place demonstrates how different choices are possible, and how market structures could be successfully (re)designed to create secure, affordable homes that value and preserve Black communities.

Innovations for scaling CLTs

Demand for secure, affordable housing is high, but so far CLTs have delivered only limited supply – about 10,000 affordable units. Grounded Solutions Network works to build more capacity and attract more funding to help CLTs meet more of the need.

“Over the next several years, we need to get to a million new units with lasting affordability,” says Grounded Solutions CEO Tony Pickett. “So we’re looking at ways to catalyze expanding CLT portfolios and the capacity of the organizations on the ground. That work is our focus over the next 10 years.”

Capital is the main prerequisite for expanding CLT portfolios. CLTs and the community-based NGOs that establish them are generally grant fundable and do attract foundation support. The NGO sector is growing, with hundreds of CLTs nationwide. But relying on grants effectively limits their growth and scope. Funding from grantmaking organizations is subject to economic disruptions, and there isn’t nearly enough of it for NGOs to operate at the scale of the need.

Some cities are investing substantial public funds in CLTs, as in Houston’s CLT bond issue and capital campaign totaling $140 million. Boston recently lost 2500 units of affordable housing in a single year when deed restrictions expired, so the City now funds a network of CLTs across the metro area. Other cities have made smaller initial investments, such as Louisville, Kentucky which put $2.3 million into developing 10 CLT units, and is working with Grounded Solutions to expand their programs.

But even though public funding is growing, depending on infusions of cash, whether from governments or foundations, places a limit on what nonprofits can do to scale CLTs. Government support can dry up when administrations change, and even if it doesn’t, government and foundations together could only provide enough funding for nonprofits to service a fraction of the potential market. For CLTs to meet more of the need will require more private capital.

“It’s not all going to come from philanthropy,” says Pickett. “Some of it will have to be in the form of financing, and patient capital is necessary in order to make that happen.” Grounded Solutions is working with banks, governments, and government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) to ramp up their investments in CLTs.

One idea Grounded Solutions is exploring is a creative acquisition fund for land trusts and land banks, modeled on a revolving loan fund the Urban Land Conservancy in Colorado uses to leverage its purchasing power. “It allows them to be opportunistic, and go out and purchase property,” says Pickett. “It has really grown their balance sheet and their ability to command larger amounts of financing.”

In the Great Recession, shared equity properties proved to be more foreclosure-resistant than properties under standard, fee-simple ownership, and therefore lower risk for lenders. That should be a compelling argument for lenders to finance more CLTs as a way to manage portfolio risk, but they are waking up to the opportunity only gradually. “Many banks, individual nonprofits, and local government officials see CLTs as some exotic mortgage product they would rather not devote time and resources to expanding,” says Grounded Solutions senior strategist Jason Webb. “We’re making inroads, but we still need broader lender education. So we’re bringing the influence of the GSEs to bear to get them to the table and help them understand how financing CLTs can actually reduce their risk of foreclosure over time.”

Since GSEs have a “duty to serve” underserved markets, they have an interest in expanding

CLTs. Grounded Solutions is working with GSEs to create standardized shared equity mortgage products that Fannie and Freddie could adopt, which would encourage wider acceptance from lenders. Some CLT loan products are offered on a limited basis in certain markets, but they are negotiated on a case-by-case basis. So Grounded Solutions is working on a Shared Equity Certification program to help national banks to underwrite these products to a uniform standard.

Standardization would be a market innovation that would unlock more lending for CLTs. There’s already precedent for it in the form of standardized leasehold mortgages, which are used for commercial properties. “Banks write them every day of the week,” says Webb. “They could write similar ones for shared equity CLT homes. It’s just a matter of overcoming how we’ve been conditioned to think about homeownership.”

“If GSEs would back the product at the same level that they’re currently backing some other affordable homeownership efforts,” says Pickett, “that would go a long way towards signaling to the industry that it’s okay, that shared equity is a normal situation we don’t have to create special conditions for.”

Besides capital, the other major factor in scaling CLTs is innovative designs that can extend their reach and make them more attractive to funders and lenders. For example, buyer-initiated purchases like HCLT’s Homebuyer Choice program are innovations that could help CLTs catch on more widely. “I think they’re going to be a huge leap forward,” says Webb. “They prove that you don’t have to be an expert in real estate development of single-family homes to be in this business in a viable way.”

Cities are experimenting with a range of CLT variations that have potential to scale up. “We don’t attempt to limit people’s imagination,” says Pickett. “If they want to use the community land trust model for farming or retail or commercial space, they’re free to do all of those things. We embrace all of that within our network.”

For example, in southeast Washington, DC’s Anacostia neighborhood, Grounded Solutions helped write an unusual business plan for the Douglass Community Land Trust (named for Frederick Douglass, who lived in Anacostia). It involves a mixed portfolio of 50% affordable rental housing (including an apartment complex renovated in partnership with the National Historic Trust) and 50% ownership housing tenants can move to once they’re ready to qualify for a mortgage. The goal is to halt displacement and ramp up the number of affordable housing units quickly, and eventually become self- sustaining. DCLT is current meeting and exceeding the plan’s benchmarks, and more City-owned property is getting transferred to it.

Like Houston, the City of Bridges Community Land Trust in Pittsburgh and the Elevation Community Land Trust in Denver are building affordable housing across their whole metro areas, including the suburbs. They’re finding that larger-scale CLTs are more attractive to funders and lenders. Economies of scale could eventually allow CLTs to become self-sustaining, so they can continue to expand without relying on uncertain infusions of cash from government or foundations. “When we talk about scale, we’re talking about power,” says Pickett. “The greater the scale, the greater the power we will have to actually change some of these systems, and ultimately help get the housing market working the way we want it to work.”

But the converse is also true: changing the way the housing market works is also a powerful path to scale. In fact, with limited funding available to expand the operations of nonprofit trusts, getting CLTs to realize their full potential may depend on their ability to model structural innovations and make fundamental changes to the market structures and policies that have impeded their growth.

Organizations like Houston Community Land Trust, Jane Place, and many others in the Grounded Solutions Network are doing the work of establishing secure, affordable housing, getting residents into it, and helping them stay in it. It’s difficult, labor- and capital-intensive work, and in terms of the direct services they provide, individual trusts may only serve a fraction of their communities’ need. But at the same time, they’re also doing something else remarkable: grappling with fundamental market problems, adapting CLTs to solve them, and redesigning market structures in the process. From buyer-initiated purchases to affordable rentals, from reforming property taxes and codifying tenants’ rights to standardizing CLT mortgage products, CLT innovators are modeling structural innovations that not only create new CLT units, but also new conditions in which CLTs and community- led development can proliferate and thrive.

That represents a new opportunity. If government, philanthropy, and finance recognized the potential of such structural innovation and invested in it, it could leverage systemic change efficiently, and create the conditions for CLTs to achieve scale and meet unmet needs. Billionaire Marc Lore, WalMart’s former e-commerce director, recently made headlines by unveiling his plan for “Telosa,” a new $500-billion utopian “city of the future” somewhere in the American desert, conceived along CLT lines. Owners will build and their sell homes while the city retains ownership of the land under them. As the land appreciates, a community-led trust will use the proceeds to fund benefits like healthcare, transportation, and schools for all residents. Lore calls it his “reformed version of capitalism.”

But we don’t have to build half-trillion-dollar desert utopias from scratch to reap the benefits of shared ownership and fundamental market reforms. Community land trusts with limited resources and innovative ideas are already demonstrating how to they can benefit Black residents and Black-majority neighborhoods across the U.S. They’re proof that key aspects of housing markets can be consciously redesigned to correct market distortions and racial inequities, lower barriers to homeownership, create secure, affordable housing, and enable community-led development without displacement.

endnotes

[i] https://reports.nlihc.org/sites/default/files/gap/Gap-Report_2020.pdf

[ii] https://www.bizjournals.com/houston/news/2021/05/10/houston-population-growth.html

[iii] https://www.houstonpublicmedia.org/articles/news/in-depth/2021/04/30/397115/rising-prices-are-making-houston-homebuyers-lower-their-expectations/

[iv] https://storage.googleapis.com/wzukusers/user-27881231/documents/5b06c0e681950W9RSePR/STR%20Long-Term%20Impacts%20JPNSI_4-6-18.pdf

[v] https://ssrn.com/abstract=3456929

[vi] https://www.huduser.gov/portal/pdredge/pdr_edge_research_041913.html

[vii] https://lafairhousing.org/new-orleanians-deserve-a-right-to-counsel/

[viii] https://nlihc.org/resource/right-counsel-expands-new-orleans-and-new-york-city

Acknowledgements

The Economic Architecture Project would like to thank the anonymous funder and the JP Morgan Chase Foundation for generous support.

The authors would like to thank Rara Reines, Steve Kent, Lael Cox, JC Ospino, Jasmyne Jackson, Elmo Tumbokon, and Sulaiman Yamin for dedicated work that made this paper possible.

Artwork and photos of the Sacred Path and Fifth Ward – Courtesy of Reginald Adams.

Design & Layout: JC Ospino / Alliter CCG