as a tool for transforming the small-dollar housing market

Download this article as PDF here.

Homes in Black-majority neighborhoods are chronically devalued.

As a result, many are priced below $70,000, which are considered “small dollar” properties. But there are few mortgages for “small-dollar” properties.

It’s a kind of Catch-22, compounding structural problems many Black buyers face in the housing market: instead of making those homes affordable and obtainable, low valuation only serves to make financing for them less accessible and more exploitive.

As of 2015, 14% of single-family homes (643,000 homes) were in the $10,000 to $70,000 price range, according to the Urban Institute. Only about a quarter of them are financed with a traditional mortgage. The rest are either bought for cash, often by speculators, or financed by other means, especially land contracts.

In The Case for Reparations, Ta-Nehisi Coates defined land contracts as “a predatory agreement that combined all the responsibilities of homeownership with all the disadvantages of renting — while offering the benefits of neither.” Also known as contract sales, bonds for deed, or contracts for deed, land contracts are a form of seller financing where the buyer puts down a down payment on the home, then makes monthly installment payments to the seller, typically for 15 years at high interest rates. The seller retains ownership of the home until all the payments have been made.

In theory, the buyer gains legal title to the home once all the payments have been made. In practice, land contracts are largely unregulated, one-sided transactions between parties with unequal power, often rife with abuse and exploitation by sellers, and often not resulting in homeownership for buyers. Using a “forfeiture clause,” sellers can terminate the land contract if the buyer misses a single payment and repossess the house, while profiting from the payments and the value of improvements the buyer made. The “buyer” is then left with nothing. Bad-faith sellers can repeat the process serially, “churning” the same property multiple times using contracts deliberately structured to make it hard for buyers to comply fully and gain title to the property. Between predatory rates and frequent forfeitures, it’s estimated land contracts extracted between $3 billion and $4 billion from Black households in mid-century Chicago.

Nonetheless, land contracts are still common, since they fill a large, structural gap in the mortgage market. Millions of households hold them, including 12% of Black households that finance a home purchase. Given how embedded land contracts are, many housing advocates argue that their abuses can’t be fixed by abolishing them.

Land contracts saw a resurgence nationwide in the wake of the Great Recession and the subprime mortgage crisis, especially in Black-majority neighborhoods with a significant small-dollar housing stock where residents have limited access to lending or capital. That’s a considerable portion of the housing market affecting millions of families. Could land contracts somehow be reformed or transformed to work for them?

Caveat emptor

In addition to chronic devaluation of housing in Black-majority neighborhoods and failure to offer mortgage products for small-dollar properties, land contract abuses are also partly explained by lax or harmful government policies.

Redlining, the federal government’s practice of refusing to insure mortgages in or near Black neighborhoods, dictated where Black people could or couldn’t buy a home.

And even long after the 1968 Fair Housing Act made it illegal to discriminate against homebuyers on the basis of race or national origin, lender practices effectively excluded Black people from buying homes outside certain neighborhoods.

This history has left a legacy of a vast number of Black homebuyers who lack access to conventional financial services. Land contracts are used to fill the gap, but they do so in a largely unregulated way.

The origin of the instrument dates back to the mid-nineteenth century, when laissez-faire economics predominated, and courts favored the notion that individuals with free will could look after themselves. Government oversight was therefore minimal and the burden was on buyers to protect their own interests – caveat emptor. But if buyers lack financing alternatives, they lack the leverage to negotiate better terms for themselves.

Today, land contracts fall under the jurisdiction of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, but its oversight remains limited. Whereas the subprime lending crisis strengthened federal regulation of mortgages, regulation of land contracts remains loose and poorly enforced. Authority over them falls mostly to cities and states, resulting in an inconsistent, inadequate regulatory patchwork that provides few protections for consumers.[i]

While there is no hard data available on how many land contracts result in home ownership for would-be buyers, there is lots of anecdotal evidence that many don’t. Most land contracts contain forfeiture clauses which quickly terminate the contract if a single payment is missed, or any other contract terms are breached. In that case the property reverts to the seller, who gets to keep everything the buyer has paid in, including the down payment, monthly payments, taxes, and insurance, plus any home improvements. The seller is then free to sell the property to other buyers.

Data on the prevalence of land contracts is also spotty, since only a fraction of them are ever officially recorded. But experts estimate 4 million families have land contracts totaling $200 billion, or about 5% of the non-rental single-family residential market.

In certain regions and cities, the relative proportion and impact of land contracts is much greater. A recent Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago study looked at the 407,237 recorded land contracts nationwide found that 69% were concentrated in six midwestern states, including 25% in Michigan. The 2009 American Housing Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau[ii] estimated that in the Detroit region, land contracts accounted for 12% of financed home purchases by African-Americans, vs. about 5% for households of other races.[iii]

In Chicago in the 1950s and 1960s, an estimated 75-95% of home “sales” to Black families were via land contract. A recent Duke/University of Illinois Chicago study found that Black buyers who entered into these contracts lost between $3 billion and $4 billion.[iv] The average price markup on homes “sold” was 84%. Buyers paid an average $587 more per month than if they had bought them with a traditional mortgage.

In Michigan, especially in the Detroit area, Black homeownership rates fell more than 20% during and after the Great Recession, from a high of about 51% in 2000 to about 40% in 2018.[v] It’s a combined effect of income loss, damaged credit, a falloff in mortgage lending, and a wave of mortgage and tax foreclosures. The City bought up foreclosed properties, then sold them in bulk at discounted prices to investors, who in turn used land contracts to resell them for high prices. For example, in 2014, a property was foreclosed for $11,200 in unpaid taxes, bought at auction for $833 by one of Detroit’s biggest bulk land buyers; then sold via land contract for $15,900.[vi] In 2015, it’s estimated that more land contracts were filed in Detroit than mortgages, though precise numbers aren’t available, since one in five land contract “sales” in Detroit is recorded.

Since they often end in foreclosure, and predatory investors continue to “churn” land contracts by “selling” and initiating forefeiture on the same property multiple times, the land contract surge in Detroit set up a vicious cycle of lowering neighborhood property values and extracting wealth from Black communities.

While there is insufficient data to know exactly how prevalent land contracts are, or how much wealth their abuses extract from Black households, there is enough data to show that land contract sales constitute a significant segment of the housing market, characterized by structural market flaws and distortions and policy failures disproportionately affecting Black people.

The question is, could they be remedied? Could the land contract market be redesigned and leveraged for better outcomes? Given its size, is there an opportunity for land contract reforms and/or new financial products to serve the small-dollar home market?

A University of Michigan / Enterprise Community Partners policy brief entitled “In Good Faith: Reimagining the Use of Land Contracts”[vii] argues that land contracts could be restructured to discourage abuse and encourage good-faith sellers. “While land contracts have an extensive and ongoing history of exploitation,” it finds, “they are not inherently predatory, and they remain an important tool for buyers and sellers alike, particularly in challenged housing markets.”

Making land contracts work for buyers

Evelyn Zwiebach sees the potential to redesign land contracts to benefit buyers and encourage good-faith sellers.

She is senior program director for state and local policy for Detroit with Enterprise Community Partners, Inc., and co-author of the “In Good Faith” report.

Enterprise is a national nonprofit which creates and invests in affordable homes, provides resident services, supports community organizations on the ground, and conducts policy advocacy. Working with local partners, Enterprise has preserved and built 793,000 affordable homes and invested $61 billion in communities nationwide.

Zwiebach fully acknowledges the failures of the land contracts, especially in Detroit: They lack transparency – an estimated 80% of them aren’t even officially reported. What federal and local regulations exist governing them are poorly enforced. The contracts themselves often don’t even meet the standard for a legally valid contract, since they omit such key information as the purchase price, interest rate, and monthly payment. And sometimes, what purport to be land contracts aren’t even land contracts at all, but even more predatory rent-to-own agreements or leases with a purchase option.

As Ta-Nehisi Coates points out, land contracts combine the disadvantages of renting with the burdens of homeownership. But Zwiebach believes it’s possible to flip that equation, and redesign them so they give buyers the benefits of homeownership on affordable, non-abusive terms. “Some community development organizations (CDOs) are acting as responsible land contract sellers,” she says. “They’ve been able to use land contracts as a way to get people who can’t qualify for a mortgage, or can’t afford homeownership otherwise, onto a path to homeownership. And they have had good success. That kind of community development approach to land contracts can help counter other types of actors in the land contract marketplace.”

And while mortgages may be preferable, they are not a panacea, either. “In an ideal world, a mortgage is almost always better than a land contract,” Zwiebach says. “But the Detroit housing market is not an ideal world. It’s not easy to get a mortgage. The mortgage industry is rife with discrimination against buyers of color, and many people just can’t qualify for one.”

Even assuming they could, obtaining a mortgage and the deed to a home doesn’t always guarantee housing security. On the contrary, since 2008, one in three Detroit homes was foreclosed[viii] on because owners fell behind on property taxes – the highest tax foreclosure rate of any U.S. city since the Great Depression. Several studies have found the lowest-valued homes in Detroit are over-assessed, putting thousands at unjust risk of foreclosure.

“The question is, how do you make homeownership sustainable?” said Zwiebach. “Will buyers in Detroit still own their home in five or ten years?” There are growing efforts to assist owners who might have been illegally over-assessed, for example by removing assessments that were too high based on their income, helping them claim a property tax exemption they qualified for but didn’t know about, or coming up with payment plans for back taxes owed. But the risk of foreclosure remains high. “Many people in Detroit who were once homeowners lost their homes,” said Zwiebach.

Since much of Detroit’s small-dollar housing stock is in disrepair, land contract buyers often struggle with the added burden of correcting deferred maintenance, and/or living in substandard conditions. “Home repair is a huge challenge,” Zwiebach says. “Especially with land contracts, people may be moving into homes that are barely habitable or have major issues. Buyers may find they can’t keep up with the needed repairs. That raises the risk they could lose the home, and it also raises health and safety hazards.”

She describes a kind of “philosophical debate” about whether land contracts are better than the alternatives: “Is it acceptable for people to buy homes with leaks and lead contamination? Many of the rental options are just as bad, if not worse. And what’s the alternative — homelessness?” In Detroit and Southeast Michigan, good-faith actors such as nonprofits and community development organizations (CDOs) use land contracts to get their clients housed, in some cases helping them buy homes that require significant repairs with land contracts, then working with them on rehab. Is that exploitive, or simply pragmatic?

“Land contracts are a divisive topic,” Zwiebach says. “Reasonable people in this space will disagree. Many people in the community development world are very passionate about keeping land contracts available as a tool, and not eliminating them by overly regulating them, or converting them into mortgages. It’s a question of striking the right balance. What can we do to disincentivize bad-faith actors, while making it easier for good-faith actors to work in this space?”

The “In Good Faith” report makes a series of recommendations for striking this balance, ranging from modest changes to sweeping ones. Some are basic legal and regulatory reforms: limiting or nullifying forfeiture clauses under various circumstances, requiring clear contract language specifying payment terms and other key provisions, recording land contracts within 30 days of signing, requiring insurance and inspections, or giving regulatory agencies more resources for enforcement. Others would shift market incentives by capping interest rates and tying them to the market index, for example floating 2% above market rates. That would lower the risk of forfeiture from usurious interest rates and discourage predatory sellers.

These are fundamental, structural changes, adding up to a kind of blueprint for redesigning the $200 billion land contract market as a viable alternative to mortgage financing which serves rather than exploits homebuyers. “Land contracts can be structured and administered to proactively promote positive outcomes for buyers,” the report finds. “In stark contrast with bad-faith sellers’ predatory land contracts, many mission-driven sellers structure what we term ‘supportive’ land contracts: land contracts marked by fair sales prices, clear terms and conditions, and supports for buyers. For these sellers, land contracts function as a community development tool, helping them increase rates of homeownership for low-income households of color and promote neighborhood stability.”

The report also recommends investing in widening access to mortgage financing through programs like Detroit Home Mortgage, which offers financing for under-appraised homes. That would help reduce reliance on land contracts. But in challenged markets like Detroit, even with expanded mortgage access, there will still be significant gaps where mortgages aren’t available or aren’t a good fit, and a need for alternative financing. Redesigning land contracts has potential to fill those gaps in a non-abusive way that benefits buyers, good-faith sellers, and communities. That would constitute a major structural shift in the small-dollar housing market.

Building a secondary market for land contracts

The “In Good Faith” report recommends a mix of reforms that would both encourage “supportive” land contracts and increase mortgage access.

Some community development organizations combine both approaches, selling supportive five- to seven-year land contracts, then working with buyers and banks to convert them to mortgages after two to five years.

“Some people think that’s a pretty interesting untapped market,” Zwiebach says, “and they have heard from banks that they’re interested in refinancing land contracts.”

That’s another way of restructuring the small-dollar market, and John Green is working to take it to scale. He is Managing Principal at Blackstar Stability. After 10 years working with large institutional clients and smaller emerging developers at a large commercial real estate investment management company in the Bay Area, he left, taking part of his team and other contacts with him, to found Blackstar. It focuses on high-impact strategies in commercial real estate and single-family housing, seeking solutions that keep families in their homes, have compelling risk-adjusted returns, and are scalable.

One of those strategies is land contracts, though Green is well aware of their flaws. “The prices these buyers pay are too high, the consumers are not protected, the property disclosures are very poor, there are no truth in lending standards, there’s a lack of transparency about the transactions, things as fundamental as reporting don’t happen, and even when they’re required by law, it’s very poorly enforced,” he says. “Texas requires recordation by law, and a study found roughly two thirds of its land contract sales are unrecorded. If you don’t know where the properties are, or who owns it, you can’t do anything about it. Many actors are intentional about keeping it that way.”

Land contract interest rates can be abusively high. Green cited one example of a $12,000 contract with a 24-year term at 20% interest. “It’s absurd; it’s like putting a mortgage on a credit card.” He sums up the economics of land contracts by quoting James Baldwin: “Anyone who has ever struggled with poverty knows how extremely expensive it is to be poor.”

But rather than trying to make the land contracts themselves more supportive, Blackstar’s approach is to refinance them on mortgages which better protect buyers’ rights, and to do it in bulk. “We buy large pools of properties that are encumbered by these contracts,” Green explains. “They’re available at meaningful discounts, and we purchase them outright on a fee-simple basis. Then we work with families to originate traditional mortgages on those properties.”

“We want to shorten the terms for buyers, and drive the interest rates ’way down,” Green said. “So we’re completing a sale transaction that otherwise wouldn’t be completed for 20 or 30 years, making them actual owners right away, and giving them the prospect of long-term ownership they rarely get with land contracts.”

The size of the pools Blackstar will buy varies from a few dozen homes to over a thousand. The sellers are typically investors getting strong returns on the properties. But they are nonetheless eager to sell. “Part of what we think motivates them at this point, despite the compelling financial returns they have realized from the land contracts, are the growing legal, regulatory, and reputational risks,” Green says.

He points to the widely publicized example of Vision Property Management, which was prosecuted for predatory practices by New York’s Attorney General, and settled for $600,000 in cash plus transferring clean titles to the families living in their New York properties. In a separate agreement with regulators, the hedge fund that financed Vision, Atalaya Capital Management, repaid $2.77 million in restitution to the consumers Vision harmed. Vision, and any companies in which its executives take a controlling interest, were barred from the residential real estate business in the state. Vision had also previously been sued for predatory practices in Wisconsin, Ohio, and New Jersey. Fannie Mae had stopped selling it foreclosed homes.

“The New York settlement was particularly aggressive,” Green says. “The AG not only penalized the operator, but reached through and penalized the hedge fund investors who backed it. That sort of thing is very chastening and has a big impact on owners’ willingness to walk through the mine field, especially in states that have demonstrated they are willing to go after land contract abuses.” After the New York settlement, Pennsylvania sought a similar one, and recently awarded 258 victims of land contract abuses the deeds to their homes, and is pursuing further compensation.

Such cases grab headlines and make an impression on market players. But that’s not the same thing as tackling the market’s structural problems. Litigation may constrain individual bad actors, but it has limited impact on the perverse incentives that attract bad actors to the market in the first place. For one thing, it isn’t always successful. And even when settlements are reached, they still have to be enforced. A year after the New York settlement was announced, some of the title transfers to families it required have yet to happen.

“The New York settlement was favorable for the families,” Green said, “but you can’t solve the problem that way. These legal avenues aren’t the solution. We think a fair opportunity to own the home with a reasonably priced mortgage is the solution.”

It’s an example of how interdiction and enforcement often fails to solve structural problems in markets, which require structural solutions. Doubling down on enforcement doesn’t change a market’s basic structure or correct perverse incentives built into it, it just increases the likelihood some bad actors might get caught. By contrast, Green’s approach of buying out land contracts and refinancing them with mortgages is a structural innovation that could restructure the small-dollar market.

But for it to catch on first requires some innovation in the mortgage market itself, which as currently configured isn’t conducive for refinancing land contracts. After all, the gap in the mortgage market and the lack of products for financing small-dollar properties is one of the drivers of land contract abuses. But there is a robust market for small-dollar second mortgages in the $40,000 to $50,000 range. Green thinks that this provides a precedent for building similar products for refinancing land contracts.

A secondary market for land contracts would be a game-changer, shifting the small-dollar housing market toward more accountable, equitable financing. Green believes it’s perfectly feasible. “We should be able to move pools of these that are performing and have been seasoned at pricing that’s comparable to second mortgage products,” he says. “The buyer should be able to expect similar yield to maturity, and it should be a reasonably liquid market.”

Building such a market would take a multi-pronged, step-by-step approach: raise the capital to buy land contract properties, cultivate a pipeline of underwriters interested in mortgage products that can refinance them, and create actual pools and products to demonstrate that refinancing land contracts with mortgages can work at significant scale.

That’s a clear pathway, which any innovator needs to go from structural insight to proof of concept to scaled change. Blackstar has clearly envisioned the steps and is working through them. It has set up an equity fund with an initial target of $100 million, and has already raised over $20 million, and it’s identifying mission-driven partners such as foundations and community development financial institutions that could contribute financing.

“Someone’s got to hold the paper long term, and there are natural prospective allies like CDFIs and CRA-motivated regional lenders that might do it,” Green says. “Our underwriting doesn’t rely on it, but there are ways of cultivating those relationships over time. The more channels we have, the more competitive mortgage products we can offer. But institutions have a much easier time underwriting actual collateral than a theory. We have to be able to show them, here’s what an actual pool looks like, here’s sufficient scale for it to matter to you, here’s the impact that you will have on these communities and these families.”

Blackstar is also talking with large companies, including a diversified financial services company, about mortgage products to refinance land contracts. Getting one institutional investor to participate can help attract others. In fact, Green sees an opportunity for large, national financial institutions to participate as well. “They have made representations about serving underserved communities, but they don’t exactly know yet how they’re going to do it, and they’re in search of solutions,” he says. “So there’s at least a willingness to engage in dialog. But they need actual products to underwrite, decide what the terms would be, and figure out how to get from the product to scale.”

As long as land contracts continue to exist, Green thinks GSEs should play an important role in refinancing them. But at the moment, GSEs are more focused on preventing land contract abuses – what Green calls “stopping the bleeding.” For example, Fannie and Freddie have restrictions preventing them from selling real estate-owned properties (foreclosed properties that didn’t sell at auction and have reverted to the lender) with land contracts. “That’s an important policy,” said Green, “but it will take a yeoman effort to enforce it, since most land contract transactions tend not to get recorded.”

Green believes that seller financing which builds in robust consumer protection could “readily address” land contract abuses, but he admits it isn’t simple or easy. “Even in some of our own offerings, we have to figure out if there’s even a way to craft a fair contract,” he says. “For example, for very small balance mortgages, the frictional costs can be untenable. But there are ways to take the asymmetry out of land contract transactions and make them less predatory. If you can do that, land contracts could be a better solution for some families and help fill the vacuum left by the lack of mortgage supply.”

Writing better land contracts and framing stricter legal and regulatory requirements and enforcement for them could make them less one-sided and more accountable. But making them work for buyers will take more than stronger legal and regulatory protections. It will also require structural innovations that shift fundamental market incentives away from exploitive, bad-faith sellers toward “supportive” good-faith sellers and responsible lenders.

Some of those innovations are emerging now. Community development organizations are writing “supportive” land contracts and working with buyers to fulfill them successfully. Practitioners like Zwiebach are coming up with ways to redesign the market, for example by capping interest rates and tying them to the market index and correcting other exploitive terms and omissions in land contracts. Both she and Green believe the mortgage market can also be innovated to impact the land contract market, both by increasing Black homebuyers’ access to financing for under-appraised properties so they’re less reliant on land contracts, and to develop a secondary market to refinance land contracts for those who can’t obtain small-dollar first mortgages. That would benefit lenders and buyers alike.

Land contracts grew out of devaluation of Black-owned assets, relegating them to small-dollar status and using it to impose predatory terms on them and to extract wealth from them, leaving their would-be owners dispossessed. But structural innovations like the ones Enterprise and Blackstar are pioneering are designed to transform land contracts from tools of devaluation and exploitation to tools of revaluation and empowerment. Rethought and restructured, land contracts may have the potential to overhaul the small-dollar housing market, secure homeownership for millions of Black families, and help preserve the value of Black-majority neighborhoods.

endnotes

[i] Toxic Transactions, National Consumer Law Center https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/pr-reports/report-land-contracts.pdf

[ii] https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/98719/rebuilding_and_sustaining_homeownership_for_african_americans.pdf

[iii] Carpenter, A., George, T., & Nelson, L. (2019). The American Dream or Just an Illusion? Understanding Land Contract Trends in the Midwest Pre- and Post-Crisis. Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, p 1. https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/media/imp/harvard_jchs_housing_tenure_symposium_carpenter_george_nelson.pdf, pg 9

[iv] https://www.npr.org/local/309/2019/05/30/728122642/contract-buying-robbed-black-families-in-chicago-of-billions

[v] https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/98719/rebuilding_and_sustaining_homeownership_for_african_americans.pdf

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] https://poverty.umich.edu/files/2021/05/PovertySolutions-Land-Contracts-PolicyBrief.pdf

[viii] https://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/detroit-housing-crisis/2019/12/05/detroit-foreclosures-effort-wayne-county-treasurer-puts-many-residents-into-deeper-debt/1770381001/ “Nearly one-third of city properties have been seized for unpaid property taxes since 2008, according to a Detroit News analysis.”

Acknowledgements

The Economic Architecture Project would like to thank the anonymous funder for generous support.

The authors would like to thank Rara Reines, Steve Kent, Lael Cox, Jasmyne Jackson, Elmo Tumbokon, and Sulaiman Yamin for dedicated work that made this paper possible.

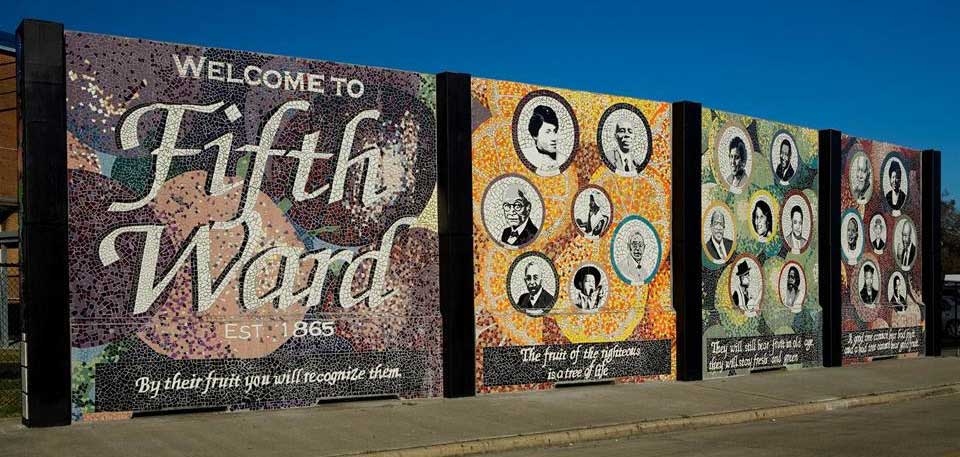

Artwork and photos of Paradise Valley terrazzo and the Ring of Genealogy installation – Courtesy of Hubert Massey

Design & Layout: JC Ospino / Alliter CCG